Transitions: Class to Class, Year to Year, P7-S1

Class to class

It is extremely important that all teachers and support staff working with children who have additional support needs are aware of the child support needs and profile. This also includes supply staff.

Information must be made available to the all of the child’s teachers through the school's confidential information sharing system, and they must access it.

Year to year

Parents regularly express concern and frustration that each year they feel that they have to repeat the process of sharing information to new class teachers about their child’s support needs and how much valuable pertinent learning and teaching time is lost for their child due to this delay. Records should be kept up to date and shared when possible between teachers. If that is not possible due to staff changes in the new academic session, information must be made available to the new teacher through the school's confidential information sharing system.

Primary 7 – Secondary school (S1)

The transition from primary school to secondary school can be daunting for children with dyslexia. Primary and secondary schools must work together to support the transition process for all children and for those who have additional support needs, planning is required to support the needs of the child. Effective communication between all those highlighted below should be in place prior to the new academic year starting in August to ensure that secondary school class teachers have up-to-date relevant information to support their class and curriculum planning.

In cases where dyslexia is a significant additional support need the transition planning must begin no later than 12 months before they enter S1 and it often the case that transition begins in P6, or sometimes earlier as highlighted in the 2010 Code of Practice.

- Arrange a transition meeting with the parents/carers, schools and child

- Listen to parents/carers and respect information shared about family links with dyslexia

- Provide supported/enhanced transition for the child

- Provide information and report from the Identification Pathway

- Ensure recording is accurate and up to date

- Ensure information is shared between P7, Primary support staff and Secondary support staff

- Ensure strategies and approaches available in primary school are discussed and supported in secondary school as appropriate

- Provide a visual timetable and ensure multiple copies are available and shared with home

- Arrange a P7 parent session at the secondary school to share school information, meet other parents and see the school

- Share curriculum information and strategies with the child’s S1 teachers by June to provide them with time for planning

- Be sensitive to the fact that the parent’s experience of school may not have been positive if they are dyslexic. It may not have been identified

- Ensure that staff have access to professional learning on dyslexia and inclusive practice

Moves from Abroad

Supporting the school transition for children and young people who have moved from abroad can be challenging for a number of reasons e.g. their educational records may not be available or may be delayed in transit.

Children and young people who are often involved in moving to Scotland from abroad may do so because of their parent/carers profession e.g. Armed Services or perhaps due to immigration/refugee support. Although they will have experienced a different education system it is important to try and find out as soon as possible from the family and child/young person their educational levels – even informally. Beware that standardised assessments may not take account of cultural differences and may not provide reliable information. If the child or young person has attended an English speaking school such as military school abroad it would be helpful to contact the school as soon as possible to discuss their profile. This is particularly important if dyslexia is suspected/mentioned or there are literacy difficulties which may be due to a history of interrupted learning but the supports can be the same.

Home to Nursery

A great deal of support is now available to help children and their family transition into nursery school. Often home visits are made and provide opportunities for parents and carers to ask questions and share concerns.

- Listen to parents/carers and respect information shared about family links with dyslexia.

- Share curriculum information and strategies, including the value of a literacy enriched home environment – developing language through, play, singing, rhymes with home.

- Share language development approaches.

- Be sensitive to the fact that the parent’s experience of school may not have been positive if they are dyslexic. It may not have been identified.

Nursery to Primary 1

Nursery staff are well placed to build up a profile of a child through observation, consultation with parents and engaging the child in the experiences and outcomes which are planned for children years through active learning. This knowledge should support the transition into P1.

- Listen to parents/carers and respect information shared about family links with dyslexia.

- Provide supported/enhanced transition for the child.

- Use of Pre-school screener /observation.

- Ensure Recording is accurate and up to date.

- Ensure information is shared between nursery and P1 teacher.

- Share curriculum information and strategies with nursery and home, including the value of a literacy enriched home environment, play, singing and rhymes.

- Share reading schemes.

- Be sensitive to the fact that the parent’s experience of school may not have been positive if they are dyslexic. It may not have been identified.

Planning and Monitoring

Curriculum Level Planning and Monitoring Considerations

Intervention at all levels is managed in close collaboration with parents, allied health professionals (if there are signs that this is warranted) and others who may be able to give support either directly or indirectly. Where a collaborative plan of intervention for a child needs to be developed, all involved parties should meet with the parents to ensure a common strategy for supporting the child. A record should be kept of any such meetings and retained with the paperwork for the Staged Process of Assessment and Intervention.

As highlighted in Section 4.1 the identification of dyslexia is not the end of the process. The assessment of dyslexia in children and young people is a process rather than an end-product. The information provided in the assessment should support the planning for the learner’s next steps and this will require monitoring due to the changes and challenges which will occur as the child grows and the curriculum develops. For example, the difficulties experienced in P6 may not be exactly the same in S3 - they may be harder or easier and other challenges may replace them.

Levels of Planning and Dyslexia

All children and young people should be involved in personal learning planning (PLP). PLP sets out aims and goals for individuals to achieve that relate to their own circumstances. They must be manageable and realistic and reflect the strengths of the child or young person as well as their development needs.

Monitoring their progress in achieving these aims and goals will determine whether additional support is working. For most children, including many who are dyslexic, a PLP will be enough to arrange and monitor their learning development. The 2010 Code of Practice says that children with additional support needs should be involved in their personal learning planning. It also says that, for many, this will be enough to meet their needs.

Some examples of PLP which support children and young people with dyslexia will be available soon.

If a PLP does not enable sufficient planning, a child or young person’s PLP can be supported by an individualised educational programme (IEP). IEPs are usually provided when the curriculum planning is required to be ‘significantly’ different from the class curriculum. Involvement with group work or extraction for a number of sessions a week does not normally meet the criteria for an IEP.

An IEP is a non-statutory detailed plan of the child/young person’s learning. It will probably contain some specific, short-term learning targets relating to wellbeing, literacy and/or numeracy and will set out how those targets will be reached. It may also contain longer-term targets or aims. IEP targets should be SMART:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Relevant

- Timed.

IEPs should be monitored regularly and reviewed and updated at least once every term with the child/young person and their parents/carers.

Examples of Dyslexia IEPs will be added shortly. If you have any examples you would like to share, please email the Toolkit team on toolkit@dyslexiascotland.org.uk

A CSP is a detailed plan of how multi agency support for a child will be provided. It is a legal document and aims to ensure that all the professionals, the child/young person and the parents/carers work together and are fully involved in the support. Dyslexia on its own as an additional support need would not commonly trigger the opening of a CSP.

In line with the 2014 Children and Young People Act and ‘Getting it right for every child’ (GIRFEC) approach, many children will now have a Child’s Plan. Child’s Plans are created if a child or young person needs some extra support to meet their wellbeing needs such as access to mental health services or respite care, or help from a range of different agencies. The Child’s Plan will contain information about:

- why a child or young person needs support

- the type of support they will need

- how long they will need support and who should provide it.

All professionals working with the child would use the plan, which may include an IEP or a CSP.

Reporting

Reporting

All those involved in reporting on the identification and assessment process should be clear about their use of language and avoid terms such as ‘tendencies’ or ‘signs’ which can potentially be confusing for pupils and parents. The Scottish Government definition of dyslexia should allow for a pupil either being dyslexic or not, but to what extent will vary along the continuum.

Where dyslexic difficulties are not presenting a significant barrier to learning, or where exploration is still in the early stages, reporting to parents/carers may be done orally at the initial stages, though clear records should be maintained of the child's progress and support. There are a number of ways in which understandings may be shared and reported - for example:

- At parents' evenings

- Through collaboration with colleagues

- Through routine pupil reports

- By means of pupil profiles; and

- Any other routine means of dissemination that are used in school.

The specific means will vary from school to school - but it is vital that information is shared regularly and transparently throughout an assessment process that is fully collaborative. The young person should be at the centre of every stage and aspect of the process of assessment and reporting.

Irrespective of the severity and stage of the progress, Staged Intervention paperwork should be completed, highlighting:

- clear notes on the teaching approaches and strategies put in place

- child/young person’s involvement

- assessment of progress made

- planning.

All records of this nature should be communicated between classes and schools.

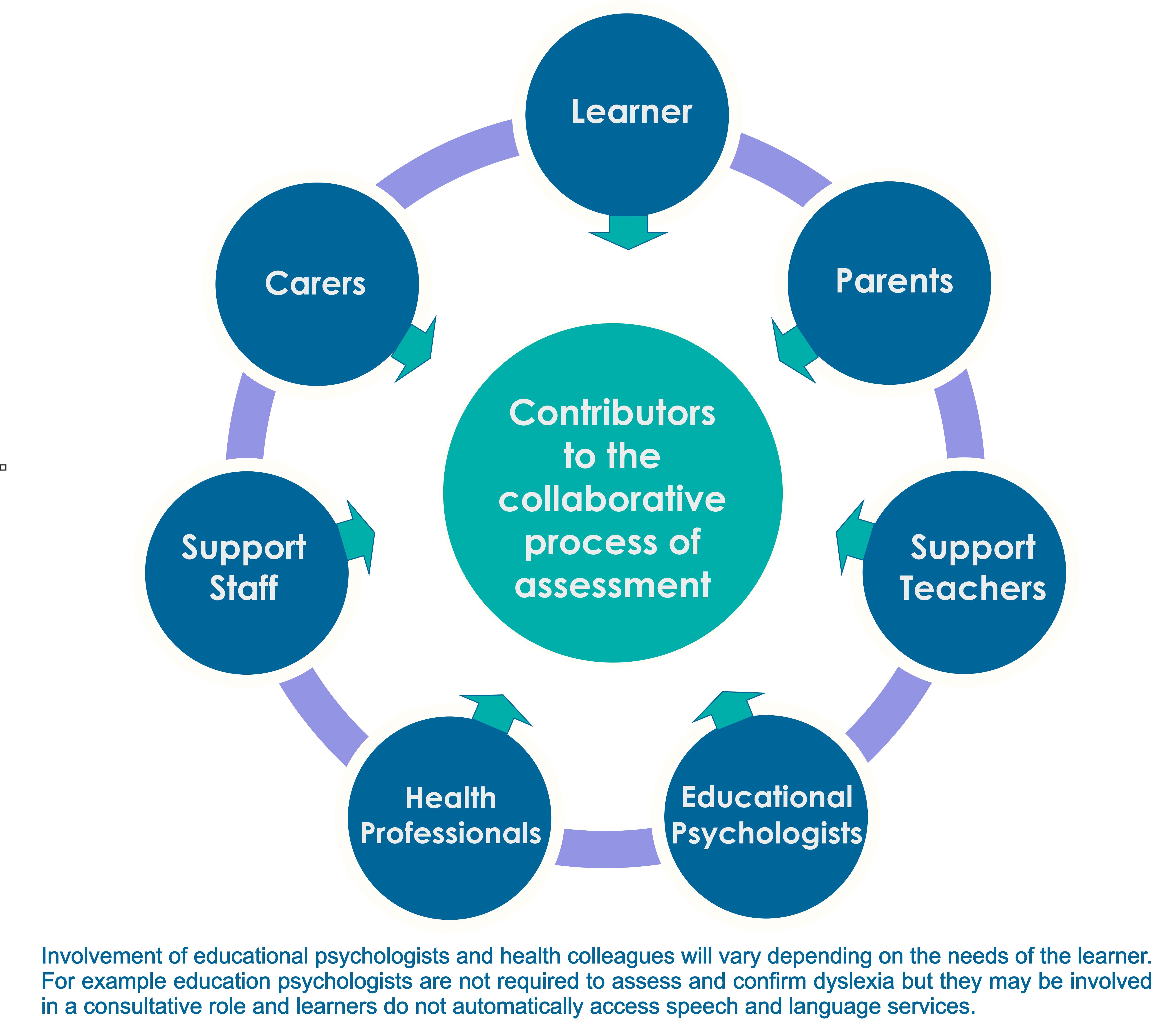

As highlighted throughout this toolkit, assessing for dyslexic difficulties should be a collaborative process which involves staff parents/carers, colleagues and the learner as fully as possible at every stage of the process. If carrying out assessments for dyslexia, the parents/carers and the young person (if old enough) should be informed.

Where dyslexia has been identified as a barrier to learning, information will continue to be shared through Parents’ evenings and other routine information-sharing mechanisms.

Reporting ranges from:

- Classroom teachers' reports – assessment is for learning

- Maintaining regular contact with parents/carers over any concerns at Step 1 through to more continuous and detailed sharing of insights at Step 2.

- A full assessment and report at Step 3, which collates and interprets all the available data and insights into an analysis/summary/report that should be helpful and informative to all those involved in helping the pupil to cope with school and post school if applicable.

Important factors to consider when reporting

- All reporting has to be done sensitively as it is important not to convey either stress or worry to parents and pupil

- Include the strengths of the learner

- Parents and carers must be treated respectfully as equal partners

- Maintain clear records of the progress of all children

- Support collaboration on what is done in school and what is done to support the school work at home. Ensure any ‘home work’ is engaging and appropriate.

- Highlight supports in place

- Include recommendations/next steps

-

All learning and teaching approaches and strategies that have been used should be recorded in the Staged Process paperwork/establishing needs form.

Parents/carers should be:

- Aware of any information that is held in paper form – including assessments

- Fully aware of what is happening

- Included in deciding the best approaches and strategies to be adopted. This needs to be dealt with in a sensitive way to avoid any possible over-reaction and distress to either the parents/carers or the pupil. Be aware and sensitive that the concern and distress will be real and may be justified.

Curriculum Level Reporting

Common types of Reporting

Early

- Informal, oral, child’s personal learning plan. Home/school jotter.

First, Second, Third , Fourth and Senior

- Ongoing and sometimes informal arrangements at Step 1 through to more continuous and detailed sharing of insights at Step 2, and a comprehensive formal report at Step 3, which collates and interprets all the available data and insights into an analysis/summary/report that should be helpful and informative to all those involved with this learner.

- Ensure there is good communication between staff in nursery and school and that records are shared.

- Maintain clear and regular communication with parents/carers. Discussions with parents may reveal a family history of difficulties which warrant further investigation. Caution will also be required as children will only be in the very early stages of developing literacy and may just be slower to acquire skills than others in their peer group. This will not prevent focused intervention and additional support if progress is slow, and the child's response to intervention monitored closely and adapted as appropriate.

- Ensure there is good communication between staff in school and that pupil profiles/records are shared.

- Maintain clear and regular communication with parents/carers. Discussions with parents may reveal a family history of difficulties which warrant further investigation or other factors which may impact on the child’s language development.

- Highlight transition support and progress.

- Ensure there is good communication between staff in school and that pupil profiles/records are shared.

- Share SQA Assessment Arrangements – this will also include support for course work.

- Share post school transition advice.

Roles and Partnership Working

It is helpful to understand the roles practitioners have within the collaborative process of identifying dyslexia.

Roles

Classroom Teacher

Support for all learners begins within the classroom and is provided by the classroom teacher who holds the main responsibility for nurturing, educating and meeting the needs of all pupils in their class. The teacher also ensures early identification of pupils' additional support needs, plans, delivers and reviews curriculum programmes.

Role of the Support for Learning Teacher (SfL Teacher)

The Support for Learning teacher works in partnership with parents and appropriate practitioners to meet the additional support needs of children and young people within their local authority's staged intervention process. They assist class teachers and school management to ensure that children who have additional needs have those needs identified and met within Curriculum for Excellence.

Support should be delivered through the five well established roles of the Support for Learning teacher:

Consultancy can take place in many forms: from simply giving advice to working collaboratively with individuals or departments. Effective learning and teaching strategies may be discussed and developed and suitable resources identified and made available.

It is important to discuss and reach conclusions on issues such as meeting the needs of learners with a variety of different needs, not just concerning literacy, but also behavioural issues. This has implications for classroom management, motivation etc.

SfL teachers may teach alongside class teachers in the classroom. Clear aims should be set out beforehand and subsequently reviewed. This helps provide direct support to, and monitoring of, the progress of all pupils in class, as well as developing classroom strategies with the subject teacher and assisting in recording and assessment.

Sometimes it is helpful for pupils, individually or in small groups, to work out of class with a member of SfL staff. This can aid the ongoing process of dynamic assessment and establish what is likely to work best. Blocks of support may be given to larger groups of pupils to focus on development of specific skills. Though this works in primary schools, it is particularly important in secondary schools in preparing learners for important exams and applying for further and higher education. SfL will be involved in planning and delivering specialised/focused programmes.

Working with colleagues to ensure the early identification of pupils' additional support needs, SfL will be involved with observations, formative and summative assessments, screening and dissemination/feedback to parents/carers/staff/multi agency colleagues.

The SfL teacher/department holds information on individual pupils and is involved in further ongoing assessment and support when this is appropriate. The SfL teacher has some delegated responsibilities for ensuring that information on individual pupils is appropriately disseminated both in school and to external agencies and parents.

Partnership working to ensure a holistic approach is taken in gathering information and placing the child/young person at the centre is very important. Support teachers will be in regular contact with colleagues in schools/educational services and multi-agency colleagues e.g. health, social work and voluntary organisations.

The SfL teacher/department contributes to staff development in a variety of ways through:

- Sharing of insight, experience and resources

- Presentation of in-service sessions, e.g. twilight sessions

- Offering guidance on accessible resources/materials, curriculum, equipment and approaches

- Sharing effective strategies, disseminating information from courses attended

- Disseminating information to staff on local authority procedures, legislation and guidelines

These 5 roles are all complementary, and none should be carried out in isolation.

Role of the Educational Psychologist

The role of the Educational Psychologist within local authority schools is to offer advice and intervention to young people, parents, schools and the Education Service. The identification of dyslexia within the school setting is not required to be carried out by an Educational Psychologist. However they may provide consultation on the assessment, identification and educational planning for pupils with dyslexia.

This may include working:

- With individual pupils and the staff who support them in contributing to the assessment process and giving advice on learning approaches.

- With staff in reviewing assessment methods and evidence of dyslexic difficulties, as well as providing staff development and training.

- At school level in validating Assessment Arrangements, as per Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) guidance.

- With parent groups, voluntary organisations, and other bodies in ensuring shared understanding of up to date developments in approaches to literacy, numeracy and other matters relating to dyslexia.

- At authority level and nationally in contributing to and ensuring that there is appropriate and effective policy and guidance, including research and development.

Education Authorities

Education authorities are required to identify and support the additional support needs of each child or young person for whose school education they are responsible. They should:

- provide transparent information and guidelines to staff and the public on their processes to support additional needs

- provide appropriate professional development opportunities

- ensure that the entitlements of Curriculum for Excellence are available and that the legal frameworks are followed.

Role of Occupational Therapist

For some children with dyslexia, their difficulties overlap into social and practical skills. Where these difficulties affect the child's everyday life, the role of the Occupational Therapist is to work with parents/carers, teachers and others to assess the difficulties the child is having with these skills. They will then work to enable the child or young person to be as physically, psychologically and socially independent as possible.

Referrals for Occupational Therapy Services can come from a variety of sources and this varies across the country. All referrers must ensure the referral is made with the parents' consent.

Role of Physiotherapist

For some children with dyslexia, their difficulties overlap with physical movement problems. Physiotherapists work with children and young people with movement disorders, their parents/carers, teachers and others. The aim of the Physiotherapist is to help the child or young person reach their full potential through providing physical intervention, advice and support.

Referrals to Physiotherapy can come from a variety of sources and this varies across the country. All referrers must ensure the referral is made with the parents' consent.

Partnership Working

There is a clear consensus that joint planning at the earliest possible stage is most helpful in meeting children's and young people's needs. Early and good communication between education staff, allied health professionals and parents is more likely to lead to coordinated and appropriate planning, support and monitoring for each individual child.

Learning targets are more likely to be reinforced at home if parents have also been centrally involved in planning. Planning is considered to be most effective when the young person's views are taken into account.

Further information can be found at:

http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Education/Schools/welfare/partnershipworking

Technology Support

Technology can help learners with dyslexia in a whole host of ways. For example, learners can:

- read more effectively by increasing font size, changing colours or by using text-to-speech or audio books

- write and spell more successfully using a keyboard or tablet with spellchecker or speech recognition

- organise school and home life and work using digital calendars, to-do lists and notes

- develop their literacy, numeracy and cognitive skills with apps and programs.

In this section we do not offer a comprehensive guide to all the technologies that can support learners with dyslexia because there are already excellent sources of information that exist.

Instead we provide a glossary of the technologies that are available and the Literacy Support Software page has a glossary of software and apps.

We offer some examples of how learners can use technology to support different aspects of learning in other parts of the Toolkit. These include:

- Writing

- Reading

- Numeracy

- Learning

For more comprehensive detail on technologies, visit CALL Scotland, Dyslexia Action and the BDA Technology web sites.

It is stating the obvious, but learners need their own device! If a pupil requires technology to read and access resources, and to write and respond, then it needs to be available to them, on their desk, when they need it. Getting up and going to the computer at the back of the class is acceptable for occasional tasks, but not if the learner relies on technology to access the curriculum and participate effectively.

Windows? ChromeBook? iPad? Android? Which is best for a learner with dyslexia?

This depends on the student, the environment and the learning tasks. You need to take all these aspects into account when considering technology. For example:

- iPads are generally simpler to use compared to a full Windows laptop and iPads also have very good built-in accessibility tools such as Speak Selection, AutoCorrect and Siri Dictation.

- In many schools, you cannot connect an iPad or Android device to the school wifi, which may be a real limitation.

- Also, the free Scottish computer voices are not available for iPad or Chromebooks.

- There are a huge number of apps available for iPads for different learning tasks and activities.

- There is currently better supportive software available for Windows laptops than Chromebooks.

- Some people find word processing and file management harder on iPads than on Windows machines.

Choosing your device(s) and software involves considering:

- The student. What are the student's skills? What do they find difficult?

- The environment. Is it one primary classroom? Or moving round a secondary school? At home?

- The task. What are the learning tasks and activities?

- The technology and technology infrastructure that is already in school. What can be connected to the school network? What are staff already familiar and comfortable with?

Providing the device and software are a small part of the intervention: teaching and supporting the pupils to use the tools effectively for learning are much more important.

Learners who struggle with reading text can use audio books to access literature. Read John and Euan's story to find out how audio books can help learners participate in class, read more, improve understanding, and achieve success with reading.

Audio books are available commercially and from charities and learners can read audiobooks on iPads, computers and smartphones.

- Listening Books and Sound Learning - audio books service - £50 per year for schools.

- Calibre and Young Calibre - a subscription-free postal service of unabridged audio books for young people with sight problems, dyslexia or other disabilities, who cannot read print.

- Audible - commercial audio books.

iTunes Audiobooks - commercial audio books.

With eBooks learners can change colours and text size, and have the text read out with text-to-speech software. eBooks come in four main formats: Kindle, ePUB, PDF and Daisy and the learner needs an app or reader software on the computer or tablet to read them.

Free eBooks

Books for All Scotland Database (accessible books for the Scottish Curriculum for learners with dyslexia and Print Disability - mainly PDF).

The Seeing Ear (online library for learners with dyslexia and Print Disability - several formats).

RNIB Bookshare (for learners with dyslexia and Print Disability - PDF, ePUB and Daisy).

Project Gutenberg (free out of copyright eBooks for anyone - several formats).

Your local library (a selection of eBooks and audiobooks for anyone - usually ePUB).

Commercial ebooks for any learner

RM Books via Glow (schools can buy or rent ePUB and PDF eBooks for learners to read on eReaders, iPad, Android and Windows).

Kindle and Amazon (read Kindle eBooks on Kindle, iPad, Android and Windows).

iTunes Book Store (ePUB books for iPhones, iPod Touch and iPad and Mac).

Google Play Books (ePUB books for Android devices, e.g. Samsung, Sony, LG etc).

WH Smith (ePUB eBooks on Kobo eReaders, iPad, Android and Windows).

Support

Teaching approaches and strategies

All children and young people need support to help them learn and develop. The needs of the child or young person should always be central to the identification, planning and provision of support. Support should be appropriate, proportionate and timely.

Appropriate strategies to enable the effective learning and teaching of learners with dyslexia should be multi-sensory in nature, well-structured and interactive. A wide range of inclusive teaching approaches, strategies and resources are used across early learning and childcare settings and schools to help learners who are dyslexic. It is important to appreciate that these can also support learners who are not dyslexic. These supports are provided within what is called 'Universal support'.

Universal Support

Universal support starts with the ethos, climate and relationships within every learning environment. It is the responsibility of all practitioners to take a child-centred approach which promotes and supports wellbeing, inclusion equality and fairness. The entitlement to universal support for all children and young people is provided from within the existing pre-school and school settings.

Some examples of universal supports are highlighted below within each of the purple boxes. Please note these lists are not exhaustive.

It is common for everyone at some point to experiences feelings of low mood, anxiety and stress. However when this is ongoing and has an impact on someone’s ability to do things then it can become a bigger problem. Some people whose dyslexia has not been recognised or supported may have feelings that cause them emotional and physical distress.

Providing a supportive child centred school ethos which nurtures positive relationships is extremely important for all learners.

- Ensure that all staff are aware of their learner's profile. Understanding the learner’s profile, maximising their strengths and supporting areas of difficulties

- Supporting the learner to understand their dyslexia - their strengths and areas of difficulties.

- Allow a range of formats for the learner to demonstrate their learning

- Mark on content – not only spelling

- Set achievable targets

- Encourage independent learning

- Peer support and buddying

- Cooperative learning which enables the learners to demonstrate their skill set and develop confidence

- Small group or individualised learning

- Specialist input from support for learning staff

Click here to access further information on Health and Wellbeing across a learning community from Education Scotland

- Supportive inclusive school ethos

- Environmental literacy audit of classroom and school

- Differentiation of materials, media, flexible means of response, individualised homework

- Multi-sensory approaches and resources

- Visual prompts, including alphabets, number lines, visual timetables

- Extra time to complete tasks

- Use of more accessible fonts on printed materials

- SQA digital question papers

- Coloured texts, paper and overlays

- Help boxes in classrooms

- Use of Toolkit literacy circles

- Literacy games

- Audio books

- Animation techniques /apps/software

- ICT to support reading and writing – (accessible digital formats)

- Encourage talking, telling stories

- Resources to support the Pre-Phonics stage

- Phonological awareness and ‘fresh start phonics’

- Graded, high-interest readers

- Reading Recovery and Writing Recovery programmes

- Cooperative learning

- Adult support, including reading and scribing

- Phonic dictionaries

- Mastery-learning spelling programmes.

Difficulties with numeracy is one of the associated characteristics within the Scottish working definition of dyslexia, but may not be experienced by all dyslexia individuals - for some it may be a strength.

Some problems with maths therefore may be related to dyslexia, however, these problems are different from, but may overlap with, difficulties caused by dyscalculia.

Supports which may help.

- Help with reading the words in the question - the learner may understand the 'how to' of numeracy but is struggling reading the text or processing the steps of the question in the right order.

- Help with the vocabulary - an illustrated maths glossary can be very useful to show that several words can have the same meaning - for example subtract, takeaway and minus.

- Hands on learning helps learners understand the why behind concepts. The use of multi-sensory, concrete, active teaching and learning opportunities (visual, auditory and kinaesthetic) to support visualisation and working memory can support the acquisition of number bonds.

- Times tables square (in class and assessments).

- Drawing dots for sharing/division.

- Addition/subtraction/time jumps etc on an empty number line.

- Visual prompts e.g. graphics of fractions, number squares, number lines, visual timetables.

- Use of memory techniques. Encouraging learners to record their working and thinking as they go will allow them to track their work and can support memory and focus. Additionally, allowing time for learners to communicate and share their thoughts/thinking is helpful as this can shift the focus onto understanding the process, and to identify if, and where, these are breaking down.

- Make it fun! Use numeracy games, talk about numbers.

- Establish if the learner understands the concept of time - do they know how to tell the time?

- Effective use of appropriate IT, for example calculators, talking calculators. Click here to see more information from CALL Scotland.

- Provide key information - this may need to be in a digital format.

- Use Digital/Write-on worksheets where possible.

- Appropriate film clips which provide a quick overview of the topic or process.

- SQA Assessment Arrangements - course work and exams (will require evidence).

For example:

- Extra time to support working memory/processing

- Use of calculator - (ensure learner is confident in how to use it)

- Digital papers

Further information on SQA Assessment Arrangements is available on their website.

Click here to download Dyslexia Scotland's leaflet, 'Ideas for supporting maths', developed for learners, families and staff. Click here to access the audio version of this leaflet.

Difficulties with organisational skills is one of the associated characteristics within the Scottish working definition of dyslexia. Time management, structuring ideas and remembering things such as names, numbers and dates may require additional time and a range of strategies. It is important to remember that we are all individual therefore not every dyslexic learner will use the same strategy as this may not work for them in the same way it works for someone else.

- Ask the learner what works for them - encourage them to explore a range of strategies.

- Provide clear step by step instructions.

- Allow for processing time.

- Provide an overview at the start of the lesson.

- Mind mapping, use of key words.

- Maximise the use of lists - written or audio.

- Memory games.

- Use of subject glossaries.

- Scaffolding techniques to support writing.

- Visual timetables.

- Colour coding.

Click here to see Dyslexia Scotland's leaflet on Mind Mapping and here to see their leaflet on Study Skills.

- Effective communication between school staff, the learner and their parent/carer.

- School strategies and approaches shared with parent/carer for home use.

- Families given the opportunity to share and approaches which work at home with the school.

- Effective communication and partnership working between practitioners - ensure that all staff working with the learner has access to their profile so they understand the learner's strengths and areas which may require some additional support.

Click here to access the resource section of the toolkit.

Further information is available to download on Dyslexia Scotland's website.

Other Factors to Consider

For a variety of reasons some children are naturally much more insecure than others at this early stage. There are many factors that will influence how a child adapts and responds to the learning environment. Inevitably, insecurity will affect the child’s learning, so it is important that the child settles as quickly as possible. If this does not appear to be happening, then close liaison with parents may be required to establish if there are factors that we need to be aware of, and take account of in teaching and supporting the child.

Children who are insecure soon become aware (either consciously or subconsciously) that they are not learning in the same way at the same pace as their peer group, and this may result in the child starting to feel "stupid" or worthless. The child may then exhibit “acting out” behaviours aimed at taking attention away from learning – clowning, “showing off”, annoying other children, or withdrawing and becoming isolated. If children’s behaviour is not diverted to other more constructive tasks and brought under control (preferably self-control) at an early stage, this can become a vicious downward cycle with lack of reward for good progress and behaviour impeding learning. It is important therefore to work with families on achieving success in some aspects of learning so that children see the rewards for their efforts as well as achievement. More detail on the types of behaviour that may be observed are considered under the three headings of Disappearing Strategies, Distracting Strategies and Disruptive Strategies in the glossary.

When considering dyslexia assessment, it is important to consider why the child is behaving in the way they are as this is not always obvious. Sometimes, it may be due to the frustrations the child feels when not learning as they feel they should, and seeing a gap between what they can do and what others can achieve seemingly without effort. It is important not to rule out dyslexia because of seemingly “bad behaviour” but to consider learning in a variety of contexts. If the child learns well at some times and not at others, or in some subject areas and not in literacy, and there is no clear reason for this, then consider the possibility of dyslexia.

For children who speak languages other than English at home, the assessment process will require very careful consideration. It is unlikely that dyslexia will be able to be clearly identified at an early age due to the child developing English as an additional language. Consideration will require to be given to the child’s first language as well as English, and this will require assistance from a professional who shares the same language as the child.

In the early years all children who are showing difficulties with emergent literacy will benefit from more focused support. Their development will continue to be monitored in the usual way, and any ongoing difficulties should be noted in order to identify appropriate approaches.

The possibility of dyslexia for children who are in Gaelic medium education will be just as relevant as it is for children in single language environments. However, the fact that the child is learning to operate in two different phonological and written language systems could be a complicating factor, and close investigation should be done before reaching conclusions. This may require focused attention to phonology in both languages. For most children English will be their home language, so consideration needs to be given to English language skills as well as Gaelic. However, the most important factor is to ensure that targeted teaching and support is given to ensure that any gap that exists between the child and his or her peer group is not allowed to grow without close monitoring, liaison with parents and agreed strategies to support the child’s development of literacy skills.

A range of assessments are available in Gaelic and these are noted at the foot of the appropriate Resources section for each level of Curriculum for Excellence.

Additionally Gaelic support material modelled on Sylvia Russell's Phonic Code Cracker material is available to help support children in Gaelic medium education. This can be used to give practice in phonic skills and can be downloaded from the Resources section - 'Downloads - Gaelic Code Cracker - Fuaimean Feumail' at each level of Curriculum for Excellence.

See the Gaelic Resources section (click on the purple strip) at the link below:

http://addressingdyslexia.org/strategies-and-resources

Children who miss a significant amount of schooling or who have not had nursery experience may exhibit signs of literacy difficulties due to missing out on certain stages in the teaching of phonological awareness, phonics teaching or vocabulary assimilation. If this has not been compensated for at home then children may have only limited experience and/or language for the learning environment they find themselves in at school. It will be important to ensure that such factors are taken into account in the observation and assessment process, and steps taken to ensure that children receive appropriate teaching to make up for the missed areas. Thereafter more informed assessment can be made.

Not all children with dyslexia will have obvious difficulties with motor skills, but even slight lack of co-ordination may influence the child’s ability to cope well with handwriting. When motor skills are affected, this often affects self-esteem as the child has difficulty with sports and physical games. Spatial awareness can be a problem resulting in the child being unaware of where on a page to start writing or reading until this skill has been overlearned.

Organisational skills are often weak in children with dyslexia. This may or may not be related to sequencing abilities, but these also are often affected, meaning that the children have difficulty in recognising order in days of the week, months etc. If the children are disorganised, and/or untidy, then it is unlikely that they will endear themselves to teachers or their peers. However strategies for organisation and sequencing can be learned and the sooner the better for the sake of the child’s self-esteem and confidence.

If there are concerns over elements of physical co-ordination or motor skills development, then referral to an occupational therapist is advised for advice and possible exercises. Referrals can come from a range of different sources, but must always be done with the parent’s consent.

Although not all young children with dyslexia have early speech and language difficulties, there is evidence that many do. Early speech and language difficulties may be indicative of later difficulties in acquiring literacy. Also dyslexia can co-occur with ongoing speech and language problems. Furthermore ongoing language problems may also be associated with reading comprehension difficulties. Practitioners need to be aware of these associations and if there are problems with a child’s speech and language, then early intervention is likely to produce the best outcome for the child.

Children may have difficulty in sounding out words and have problems with phonological awareness. A case history of early development and information about early/ previous/ ongoing input from Speech and Language Therapy is helpful.

Children with dyslexia may be able to say a word but cannot break it down into syllables and/or sounds. They may have difficulty working out the constituent sounds in a word (e.g. they are unable to blend d-o-g to make ‘dog’). For others, their auditory awareness of sounds is impaired, so they are unable to say where in the word a sound comes (e.g. they are not aware that the /b/ sound in ‘boy’ comes at the start). For those children, training in auditory discrimination is vital if they are to be able to learn phonics successfully.

If there are concerns over elements of speech and language development, then referral to a speech and language therapist is advised for advice and appropriate management. Referrals can come from a range of different sources, but must always be done with the parent’s consent.

While dyslexia can affect children from all different types of background and cultures, it is important to take account of those factors. In some cultures such as that of Gypsy/Travellers, oral traditions are much stronger than written. Children may be brought up in homes where there are few, if any, books. Culture will influence the value that families place on reading and writing. Liaison with parents and carers will help establish how literacy is valued and the types of literacy that are important to the family. It is also important to talk to the children about the types of literacy that are valued in their homes. This may help explain any difficulties that children are having but it should not rule out the possibility of dyslexia.

Children may have motor and/or perceptual problems with vision that could cause them to have difficulties in following text and learning to read. Thus, improving vision can have a very positive effect on the child's progress in gaining literacy. Though visual problems are not likely to cause dyslexia, if they are present they will certainly aggravate pre-existing difficulties. Examples of the types of problems that may be present are visual stress/Meares-Irlen Syndrome, poor vergence control, scanning/tracking problems and poor binocular vision. Symptoms of visual problems may include:

- eye strain under fluorescent or bright lights

- glare

- same word may seem different or words may seem to move

- headaches when reading, watching tv, smart phone, tablet screen, computer monitor

- patching one eye when reading

- difficulty tracking along line of print causing hesitant and slow reading.

It is sometimes difficult to assess if a child has any visual difficulty at an early age. However if the child is rubbing his/her eyes a lot, seems to have difficulty in focusing and tires easily when doing close book or computer tasks, then observe if these difficulties are also present when playing other games or listening to a story (without following in book). If the child has these difficulties, then it would be best to seek professional advice from a qualified orthoptist, but report the circumstances under which the child is apparently struggling.

There are clinics at most main hospitals and referral can be made through the student’s GP, educational psychologist or the community paediatrician. Treatment may involve eye exercises and/or the use of colour – either tinted spectacles or the use of a coloured overlay.

What to look for - Curriculum for Excellence levels

Ongoing assessment, including in the senior phase, will include assessing progress across the breadth of learning, in challenging aspects and when applying learning in different and unfamiliar contexts. A class teacher’s valuable insight and observations contribute significantly to the provision of appropriate curriculum planning, assessment and supporting learners with additional support needs.

Assessment within the context of Curriculum for Excellence is also assessment for additional support needs. They should be considered to be two different or completely separate types of assessment.

When beginning the process of assessing the child or young person’s needs the areas below need to be considered, however be mindful that depending on the age and stage of the learner not all areas may be applicable.

- Processing of language-based information (auditory and/or visual)

- Phonological Awareness

- Oral language skills and reading fluency

- Short-term and working memory

- Sequencing and directionality

- Number skills

- Organisational ability

- Motor skills and co-ordination

You may find the following checklists helpful. Please note that the purpose of the checklists is to guide initial gathering of evidence to support the collaborative process using the dyslexia identification pathway. The checklists do not provide an identification of dyslexia. It is recommended that a copy of the completed checklist should be kept in the learner’s records to inform appropriate future planning.

What to look for Early Level Checklist

What to look for First and Second Level Checklist

What to look for Third, Fourth and Senior Checklists

Scottish Dyslexia Planning Tool

A range of templates to support the collaborative and holistic identification, support and planning process are available to download for free in the Resources - Identification Forms and Templates section

Read more:

Starting the Process

Early Level

At the pre-school stage in a child’s development, a great deal of caution should be exercised. Children all develop at different rates and sometimes a child will seemingly be coping fine, but later for no apparent reason will start to stumble and then have significant difficulty. This might be because they have learned to recognise a few words by their appearance or shape, but don't have the phonic knowledge to decode. Once in school, when the number of words starts to increase, without the phonic knowledge, the child becomes muddled and even the words that were apparently known become problematic. For children who have had the optimum literacy rich environment within an appropriate context of play and fun, difficulties may only become apparent at a later stage. The purpose of making observations and taking action at this early stage is:

- to ensure we maximise opportunities for literacy learning and development

- to acknowledge that underdeveloped phonological awareness may be an indication of dyslexia

- to address concerns at the earliest stage and to collaborate with parents and other caregivers involved in the child’s life and education.

Most of these difficulties can be observed within the context of experiences and outcomes in Curriculum for Excellence. Others can be observed in the routine of the nursery or classroom. It should be noted that we are looking for a pattern or profile of difficulties and not just one or two.

Most young children will exhibit some of the signs of dyslexic difficulties. It is therefore important that we look for a cluster of characteristics which may indicate dyslexia and that we do not jump to conclusions prematurely when pupils show only one or two indications.

Dyslexic difficulties will be at different levels of severity, requiring different levels of response and intervention. Observation and detailed assessment will be required within Curriculum for Excellence to identify specific strengths and development needs before any conclusions can be drawn.

First, Second, Third, Fourth and Senior Levels

There may be a number of reasons why a child or young person may experience difficulties in any of the curriculum levels which may or may not be dyslexia. When starting the process of exploring if dyslexia is a causal factor it is important to take a child/young person centred approach looking at the Scottish working definition of dyslexia and considering if there is a correlation between this and their difficulties. For example this may include learning to read, write, spell or developing short-term and working memory skills. (These difficulties may vary in severity from child to child and may seem out of sync with the child’s other abilities – e.g. oral, artistic, creative, emotional).

The Scottish working definition of dyslexia includes a range of associated factors which are highlighted below. You can select each one to see a range of questions linked to curriculum levels which can help to develop further understanding of areas which the child or young person experience difficulties with in regards to dyslexia.

At First and Second Levels does the child seem to have difficulties auditorily in distinguishing sounds/syllables/words and identifying where they heard them in words/sentences?

At Third, Fourth and Senior levels in addition to above this may also be more apparent in foreign language learning.

Does the young person sometimes misread or misunderstand apparently straightforward instructions or text?

What about visual processing? Are there any difficulties in getting letters and words the right way round, following text, copying letters/words?

At First and Second Levels does the child seem to have difficulties in sound matching or remembering specific sounds and manipulating them in words, sentences, and understanding how the sound system of language works?

At Third, Fourth and Senior levels in addition to above this difficulty is likely to be much more apparent in the learning of other languages.

Are there any apparent difficulties with speech production, muddling words or pronouncing words when reading?

At First and Second Levels can the child remember language-related information in particular - such as instructions, letter/sound correspondences, words, tables - and can they hold information while they do other things?

At Third, Fourth and Senior levels in addition to above can the young person remember language-related information in particular - such as instructions, formulae, phone numbers, pin numbers, tables - and can they hold information while they do other things?

How does the child cope with remembering sequences of instructions/days of the week and getting things in the right order? Do they understand the difference between left and right and remember which is which? Do they easily become disoriented?

Is the child able to work with numbers and do simple tasks that require recognition and memory?

How well can the child organise him/herself? – e.g. planning for gym, getting changed, tidy desk etc?

Additional things to consider

Are there any difficulties with motor skills (fine or gross) and/or co-ordination? Is handwriting affected? How does the child cope in the gym?

Consider self esteem, stress levels, behaviour factors, low achievement. Is it possible that problems with motivation to learn are a result of difficulties that could be associated with dyslexia?

In addition, it is important to consider if there could be any other reasons why children are not achieving the desired outcomes or giving the desired responses. Consider for example:

Your teaching:

- Did I present this in a clear manner?

- Did I talk too quickly?

- Did I gain the child’s attention?

- Did I make assumptions about the child’s prior knowledge?

- Developmentally was the child ready for this?

- Did I talk beyond the child’s concentration span?

- Was the child interrupted or distracted by anything or anyone?

If there are ways in which you can change your language and/or teaching to support the child’s learning, then this is probably the first course of action.

The classroom:

- When I am talking, are children seated so that they can all see me without having to turn their heads?

- Is the classroom welcoming?

- Do the children know how to locate their belongings easily? Do they recognise them?

- Is there an appropriate place to change shoes and store belongings tidily?

- Can I make the walls more dyslexia friendly? (Too much visual material can be confusing if a child doesn’t understand what it is about.)

- Do I consider the social mix of children within groups so that children can feel supported without feeling their abilities are underestimated?

- Do I encourage a range of metacognitive styles?

- Are there appropriate consistent daily routines so that the child knows what to expect?

Children with difficulties are often easily disorientated so require consideration to be given to aspects of seating. It is important that they are able to receive attention without having to turn around to see the board or the teacher. Visual impact is also improved when there is clear organisation within the classroom, including the classroom walls.

Read more: