Terms and conditions

Terms and Conditions of use

Access to and use of these sites (www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.unwrapped.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.addressingdyslexia.org ) is provided by Dyslexia Scotland, a company limited by guarantee in Scotland (company number 153321) and having its Registered Office at Dyslexia Scotland, 2nd floor – East Suite, Wallace House, 17-21 Maxwell Place, Stirling, FK8 1JU and a registered charity in Scotland (SC000951) subject to the following terms:

By using www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.unwrapped.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.addressingdyslexia.org, you agree to be legally bound by these terms, which shall take effect immediately on your first use of each of these websites. If you do not agree to be legally bound by the following terms please do not access and/or use the websites.

Dyslexia Scotland may change these terms at any time by posting changes online. Please review these terms regularly to ensure you are aware of any changes.

Copyright

You may not copy, reproduce, republish, download, post, broadcast, transmit, make available to the public, or otherwise use www.enable.org.uk content in any way except for your own personal, non-commercial use. You also agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.unwrapped.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.addressingdyslexia.org content except for your own personal, non-commercial use. Any other use of the content from these websites requires the prior written permission of Dyslexia Scotland.

Intellectual Property

The names, images and logos identifying Dyslexia Scotland are subject to copyright, design rights and trademarks of Dyslexia Scotland. Nothing contained in these terms shall be construed as conferring by implication, personal bar or otherwise any licence or right to use any trademark, patent, design right or copyright of Dyslexia Scotland.

Where you are invited to submit any contribution to www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.unwrapped.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.addressingdyslexia.org (including any text, photographs, graphics, video or audio) you agree, by submitting your contribution, to grant Dyslexia Scotland perpetual, royalty-free, non-exclusive, sub-licensable right and license to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, perform, play, make available to the public, and exercise all copyright and publicity rights with respect to your contribution worldwide and/or to incorporate your contribution in other works in any media now known or later developed for the full term of any rights that may exist in your contribution, and in accordance with privacy restrictions set out in Dyslexia Scotland’s Privacy Policy.

If you do not want to grant to Dyslexia Scotland the rights set out above, please do not submit your contribution to www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.unwrapped.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.addressingdyslexia.org

Contributions should:

• be your own original work

• not be defamatory

• not infringe any law

Disclaimer Statement

We hope that the www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.unwrapped.dyslexiascotland.org.uk; www.addressingdyslexia.org websites will be of interest to you, but we accept no responsibility and offer no warranties in relation to the content of the website and your use of it, to the fullest extent that the law permits us to exclude such liability.

All use of our website is subject to Scots law and the jurisdiction of the Scottish courts and is subject to this disclaimer. Any views expressed in messages or images on our website are not necessarily those of Dyslexia Scotland or anyone connected with us. We do not necessarily endorse any of the products referred to directly or indirectly on our website.

Our sites may contain links to and from the websites of our partner networks, advertisers and affiliates. When you access any other website through our websites you must understand that it is separate from Dyslexia Scotland, and that we have no control over the content or availability of other websites. If you follow a link to any of these websites, please note that they have their own privacy policies and that we do not accept any responsibility or liability for these policies. Please check these policies before you submit any personal data to these websites.

In addition, even although there is a link to another website from our own website, this does not mean that Dyslexia Scotland endorses or accepts responsibility for the content, or the use of, such a website and we shall not be responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused by or in connection with your use of or reliance on any content, goods or services available on or through any other website linked to or from our own. Any concerns regarding any external link from our website should be directed to its website administrator or webmaster.

Further Information

For further information or clarification, please contact us.

Dyslexia Scotland

1st floor – Cameron House

Forthside Way

Stirling FK8 1QZ

Email: info@dyslexiascotland.org.uk

01786 446650

Email: info@dyslexiascotland.org.uk

Accessibility

We have made this website as accessible and usable as possible. We've done this by adding Recite Me’s accessibility and language toolbar to our website as well as following the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0) produced by the World Wide Web Consortium, W3C, the web's governing body.

ReciteMe is a third party accessibility service. For help using it see the user guide.

Feedback

If you have any problems with the accessibility of this site or suggestions for improvement then please do not hesitate to contact us. We will always do what we can to make our site easier for everyone to use.

Privacy policy (website)

This privacy policy sets out how Dyslexia Scotland will use and protect any information that you provide when you use this website.

Dyslexia Scotland wants to respect your privacy and to protect any personal information that you give to us. This policy is made in order to comply with the provisions of the Data Protection Act 1998 and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) from 25 May 2018 to tell you how Dyslexia Scotland will use any personal information that we collect from you.

For the purpose of the Data Protection Act 1998 (the Act) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) from 25 May 2018, the data controller is Dyslexia Scotland, Wallace House, 17-21 Maxwell Place, Stirling FK8 1JU.

Dyslexia Scotland may change this policy from time to time by updating this page. You should check this page from time to time to ensure that you are happy with any changes. This policy is effective from May 2018.

How do we collect information?

We get personal information about you when you enquire about campaigns that we run, or other things that we do; or if you register with us to take part in an event or competition; if you contribute stories, articles or artwork or make a donation, take part in a poll or survey, or give us personal information in any other way.

What information do we collect?

The types of personal information we might ask for may include your name, address, gender, email address, telephone number, credit/debit card or direct debit details (if you are buying anything through us such as membership).

- demographic information such as postcode, preferences and interests

- other information relevant to satisfaction surveys or interest and opinion polls

How do we use your information?

We will always ask you if you want to give us your personal details, and ask your permission about how we use it.

If you agree, we will use the information that you give to us

- to send you information, products or services that you have asked for

- to look at how we can make the information, products and services we offer to you better (including this website)

- to contact you about events, fundraising, campaigning and our other work

- From time to time, we may also use your information to contact you for evaluation purposes. We may contact you by email, phone or post.

- We use Google Analytics to track the number of visitors to our website. These are anonymous statistics and no personal records will be generated based on this analysis.

We may sometimes contact you with offers from companies that work with Dyslexia Scotland which may be of interest to you.

You can change your mind about how we share your information at any time by contacting:

Dyslexia Scotland

1st floor – Cameron House

Forthside Way

Stirling FK8 1QZ

Email: info@dyslexiascotland.org.uk

Do we use 'cookies'?

'Cookies' are small pieces of information sent to your computer and stored on your hard drive to allow an organisation who owns the website to know who you are when you next visit the website.

Dyslexia Scotland may store information about you and your activity in cookies. The only cookies that we use will be for use with Google Analytics so we can offer the best possible user experience when you visit our site. If you want to delete any cookies that are already on your computer, please read the instructions for your file management software to find the file that stores cookies.

If you want to stop cookies being filed on your computer in the future, please read your internet browser's instructions. Please note that by deleting or disabling future cookies you may not be able to use certain parts of our site.

What happens when you link to another site?

This Privacy Policy applies to Dyslexia Scotland websites (Dyslexia Scotland; Dyslexia Unwrapped; Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit) only. The Dyslexia Scotland websites have links to other websites owned by other people. Dyslexia Scotland does not pass on any personal information about you to any other website when you link to another website from this one.

If you use a link from the Dyslexia Scotland websites to another website you must read the privacy policy of that other website to know how they may use any personal information that you may give to them.

How do we protect personal information?

We will make sure that any personal information that you give to us is kept secure, accurate and up to date, and only keep it for as long as it is needed and only for the purposes for which you have agreed we can use it.

Under 13 year olds

If you are 13 or under, please get your parent/carer/guardian's permission before you give us any personal information about yourself.

Your consent

By giving us any personal information you are agreeing to our use of that information as it says in this Privacy Policy.

Right of access

You have the right to ask for a copy of the information that we have about you.

Also, if any information that we have about you is wrong, you can ask us to correct it for you.

Changes

If your personal details change, please help us to keep those details up to date by telling us about any changes.

If you want to see what information we have about you, or need to tell us about any changes to the information that you have given to us, please contact:

Dyslexia Scotland

1st floor – Cameron House

Forthside Way

Stirling FK8 1QZ

Email: info@dyslexiascotland.org.uk

We may change this Privacy Policy at any time. If you use this website after changes are made you will be agreeing to those changes.

Dyslexia Scotland, 1st floor – Cameron House, Forthside Way, Stirling FK8 1QZ Tel: 01786 446650. Registered Charity Number SC000951

Q-Z

Glossary (including acronyms)

No glossary terms.

Reliability

The extent to which a test or assessment can be depended on; the extent to which the test gives the same results when used under the same or similar circumstances on different occasions.

Rhyme

A string of letters at the end of words which sound the same e.g. which and rich.

Rime

The group of letters in a syllable following the onset.

Generally speaking the rime is the part of the syllable that begins with the vowel and comes after the onset e.g. ay in play or say.

RMPS

Religious, moral and philosophical studies

Screening

Screening typically consists of looking at a group of indications that may mean that a child is showing signs of being dyslexic. It is not the same as a dyslexia assessment that will involve thorough investigation of the child’s cognitive functioning as well as considering various other factors. Screening can however indicate that a child requires specific help or intervention that can then be monitored and, if appropriate, full assessment can follow later. Screening can often be done with groups of children rather than individually.

SfL

Support for learning

SpLD

Specific Learning Difficulties (to differentiate these difficulties from more general learning difficulties).

Spoonerism

Transposition of initial or other sounds or two or more words – e.g. wellie boot ⇒ bellie woot.

SQA

Scottish Qualifications Authority

Suffix

Element added to end of a word to qualify its meaning.

Syllable

A pronouncable ‘beat’ in word, unit of spoken language.

Text (A Curriculum for Excellence)

The medium through which ideas, experiences, opinions and information can be communicated. Examples of texts include novels, short stories, plays, poems, reference texts, the spoken word, charts, maps, graphs and timetables, advertisements, promotional leaflets, comics, newspapers and magazines, CVs, letters and emails, films, games and TV programmes, labels, signs and posters, recipes, manuals and instructions, reports and reviews, text messages, blogs and social networking sites, web pages, catalogues and directories.

No glossary terms.

Validity

The degree to which a test actually measures what it says it does - the extent to which the tool is 'fit for purpose'. There are several types of validity. No attempt has been given here to define all of them here.

Visual

Seen or perceived by the eyes.

Vowel

The letters a, e, i, o, u. Y can behave like a vowel when it makes an ĭ or an ī sound as in happy or sty.

No glossary terms.

No glossary terms.

I-P

Glossary (including acronyms)

IEP

Individualised Educational Programme

Independent assessment (SQA)

An instrument of assessment applied by the awarding body to improve the rigour and credibility of assessment decisions across different awarding bodies and centres.

Individualisation

Modification to suit the wishes or needs of a particular individual.

Instruments of assessment (SQA)

A means of generating evidence of a candidate's competence. Sometimes referred to as 'approaches to assessment' or 'assessment methodology', eg observation checklist, project specification or peer report.

Integrated assessment (SQA)

Where the application of an instrument of assessment allows for assessment of more than one Unit within a qualification.

Internal assessment (SQA)

Where the application of an instrument of assessment allows for assessment of more than one Unit within a qualification.

Internal Verifier/ Moderator (SQA)

The person within the centre who checks that the assessment process has been valid, reliable and practicable.

No glossary terms.

No glossary terms.

Literacy (A Curriculum for Excellence)

The set of skills which allows an individual to engage fully in society and in learning, through the different forms of language, and the range of texts, which society values and finds useful.

Meares-Irlen Syndrome

Also known as ‘Irlen Syndrome’ and ‘Scotopic Sensitivity Syndrome’, it is a perceptual problem that seems to upset the way the brain processes incoming visual information with various detrimental results - for example, print seeming blurry, perhaps seeming to move around and/or peculiar patterns or ‘rivers’ seeming to appear. It is not an optical problem nor does it affect only those with literacy difficulties, but can it be exacerbated by factors such as bright lighting, high contrast, glare, patterns and colours. It can affect not only reading and writing ability, but also fluency, comfort, concentration and attention, and therefore comprehension and behaviour.

Metacognition

Awareness of, and understanding how we think and process information; thinking about thinking.

Multisensory

Using all of the available senses to aid learning – hear it, see it, say it, write it: - do it, act it out, shape it with dough, trace it, type it on the computer, feel it etc.

Neurodevelopmental

The development of the nervous system; relating to the development of cognitive functioning.

Onset

The initial consonant(s) of a syllable e.g. spr in spring, or p in pat.

PE

Physical education

Phoneme

A distinguishable speech sound.

Phonological awareness

Sensitivity to the sounds of language. It includes the ability to segment and distinguish individual and groups of sounds - i.e. phonemes, syllables etc.

It is generally agreed that phonological awareness links to children’s reading development at three levels

- Syllable

- Onset-rime

- Phoneme.

Phonology

Relating to the sound system of the language.

PLP

Personal Learning Plan

Prefix

Element placed at start of a word to qualify its meaning.

Assessing & Supporting Dyslexia: Glossary (including acronyms)

A-H

Accommodations

Enabling arrangements which are put in place to ensure that the dyslexic person can demonstrate their strengths and abilities, and show attainment.

AHP

Allied Health Professional – e.g. Speech and language therapist, Occupational therapist, Physiotherapist, Clinical psychologist, Orthoptist, Dietician, Family therapist, Art therapist.

ASL

Additional support for learning

ASN

Additional support needs

Assessment (SQA)

The process of collecting and interpreting evidence of candidate performance.

Assessment arrangements (SQA)

Alternative instruments of assessment and/or support to enable a candidate to demonstrate competence against the qualification standards.

Assessment of literacy difficulties

The assessment of literacy difficulties typically involves a combination of formative, observational and standardized assessment. It will consider a child’s progress in a range of skills and any barriers to learning in reading, spelling and written work. A complete profile of the strengths and weaknesses is built up, and factors that may seem to be peripheral to the essential literacy skills are also considered.

Assessment on demand (SQA)

The use of the assessment process to confirm competence without requiring candidates to undertake any further training.

Assessor (SQA)

The person who applies the assessment process to candidates for their achievement of a qualification.

Assessor and Verifier Units (SQA)

Nationally-devised Units which centre staff can complete to prove their competence in the assessment process.

Atypical behaviour

Behaviour that is deemed to be out of character or abnormal.

Auditory

Heard or perceived by the ears.

No glossary terms.

Consonant

Letters that are not vowels, produced by a momentary stoppage of air as the sound is pronounced.

The following working definition of dyslexia has been developed by the Scottish Government, Dyslexia Scotland and the Cross Party Group on Dyslexia in the Scottish Parliament. This is one of many definitions available. The aim of this particular working definition is to provide a description of the range of indicators and characteristics of dyslexia as helpful guidance for educational practitioners, pupils, parents/carers and others.

Dyslexia can be described as a continuum of difficulties in learning to read, write and/or spell, which persist despite the provision of appropriate learning opportunities. These difficulties often do not reflect an individual's cognitive abilities and may not be typical of performance in other areas.

The impact of dyslexia as a barrier to learning varies in degree according to the learning and teaching environment, as there are often associated difficulties such as:

- auditory and/or visual processing of language-based information

- phonological awareness

- oral language skills and reading fluency

- short-term and working memory

- sequencing and directionality

- number skills

- organisational ability

Motor skills and co-ordination may also be affected.

Dyslexia exists in all cultures and across the range of abilities and socio-economic backgrounds. It is a hereditary, life-long, neurodevelopmental condition. Unidentified, dyslexia is likely to result in low self esteem, high stress, atypical behaviour, and low achievement.

Learners with dyslexia will benefit from early identification, appropriate intervention and targeted effective teaching, enabling them to become successful learners, confident individuals, effective contributors and responsible citizens.

Differentiation

The adjustment of teaching and learning to suit the learning needs of pupils.

Differentiation can be to suit:

- the whole class

- particular groups

- particular individuals.

Differentiation can be:

- by task (different tasks for different student levels)

- by outcome (setting different expectations and/or tasks) or

- by support (giving more help and/or accommodations).

Differentiation should enable all pupils to learn.

Digraph

Two letters that make one sound. There are vowel digraphs and consonant digraphs (e.g. ea [vowel digraph] as in ear, ch [consonant digraph] as in church).

Disappearing Strategies

Children who have a quiet disposition may adopt the strategy of becoming a ‘Disappearing Child’ in the classroom, by being exceptionally quiet and not drawing attention to themselves at all. They avoid eye contact with the teacher and do not put up their hands to ask or answer questions. Many will perfect a performance that makes it seem as if they are engaging in a task appropriately. They will appear to be writing or reading even though they may have a poor grasp of what the task entails or may not have the skills to accomplish the task. In a busy classroom such children may be difficult to identify for a considerable time which means that they may be lagging far behind peers once they are identified.

In some cases a child will develop a strategy that means they are physically not in the classroom when a particular task occurs, most often reading aloud, which dyslexic children find the most frightening aspect of the classroom. This strategy may take the form of being particularly helpful, so the child may volunteer to take the register to the office or to take messages around the school to other teachers. They will perhaps take rather longer than is necessary to complete such tasks in the hope that the activity that they are trying to avoid will be finished by the time they return. Some children use the pretext of frequent and extended trips to the toilet to achieve the same aim. Teachers should be alert to the timing of these activities. Is there a pattern for example in a child’s behaviour that suggests s/he is concerned about a particular task? At the extreme of the continuum of ‘disappearing’ strategies a child may use illness as a mechanism for avoidance so a pattern of absence related to the timetable may alert either teachers or parents to the child’s underlying difficulty.

Disruptive Strategies

If a child does not have the verbal confidence to become the ‘Class Clown’, or the sporting prowess to aim for ‘Team Captain’ status, then being a ‘Disruptive Child’ may seem a reasonable alternative. Again, as adults we can see how misplaced a strategy this is, but children do not have such a long-term perspective and focus mostly on resolving their immediate difficulties. If the dilemma is how to avoid failing at a particular task, especially in front of friends, then standing outside the door of the classroom as a result of obnoxious behaviour is actually a reasonable solution to the immediate problem. Again, children who adopt such behaviour may well be popular with their peers as watching someone else get into trouble is entertaining but presents no personal risk to members of the ‘audience’.

At the extreme of the continuum of disruptive strategies are the children whose behaviour leads to them being excluded or those who play truant in order to avoid the stress of facing tasks in the classroom that they cannot complete. This of course means that they have also, quite literally, ‘disappeared’. Such extreme strategies tend to occur if some of the other strategies have not elicited the recognition and support that the child needs. By this time the child is likely to have developed ‘learned helplessness’ which is a state in which an inability to undertake particular activities undermines confidence in all tasks, even those that could be accomplished successfully. Such children, though rare, are at this stage ‘lost’ to education as they feel no sense of engagement or ‘belonging’ in a context that has failed to meet their needs.

Children tend to be pragmatic creatures. In reality the child's day to day life in the classroom would be easier if s/he simply undertook the tasks presented so we must conclude that if a child could complete text related tasks, s/he would - simply because it is easier to do so. If a child persists in not completing tasks successfully in the classroom then we should assume that there is likely to be an underlying reason for such behaviour. One possible explanation is that the child is dyslexic and therefore needs additional support in order to develop the text related skills required.

Distracting Strategies

For dyslexic children who have good verbal skills the preferred strategy is often that of becoming ‘The Class Clown’ – the child who is always ready with a quip or a joke. On the face of it this behaviour is not likely to endear the child to a teacher but it is likely to result in a high level of peer approval and for a child who feels that he is unable to do what the teacher requires, being popular with peers may seem a worthwhile alternative. This strategy also distracts everyone from the task that the child may fear and is an attempt to avoid being seen to fail by the peer group.

If a dyslexic child is skilled at sport then a focus on that activity may also serve to distract teachers from the child’s difficulties with classroom tasks. Such children often maintain high self-esteem and peer group approval despite having difficulties with text based tasks so there is a possibility that engagement in the sporting activity may lead to difficulties in other areas being overlooked.

No glossary terms.

No glossary terms.

No glossary terms.

No glossary terms.

Parents: Q&As

Questions parents often ask

The questions below are all real questions from real parents/carers. The answers to these questions have been provided by the Working Group, all of whom are involved professionally with children and young people with dyslexia. Names have been changed so the real children remain anonymous. The working group has organised the questions under headings but there is considerable overlap between headings.

Q. I think my son/daughter might be dyslexic. How do I find out? Do I need an assessment? If so, who will do it?

A. The first step if you think your child may be dyslexic is to approach the school. In the first instance, you should talk to the support for learning co-ordinator who will generally be a member of the school's management team and will be able to gather information to establish if teachers also feel your child may be dyslexic. Assessment is generally carried out over a period of time through a staged process of investigating the difficulties the child is having, and considering how they respond to specific interventions and support. The term 'dyslexia' is used once it has been established that the difficulties are likely to be ongoing and persistent, and the child or young person is likely to need ongoing support.

Q. I've been told my child is probably dyslexic as s/he has been struggling with written work, especially spelling, all through school. Do I have to give my agreement to her/him being assessed?

A. If your son is to get the help he needs, and he understands the process, then it is advisable that he should be assessed. He has a right to know, and assuming that he wishes to know if he is indeed dyslexic, then the best advice is to agree to assessment.

Q. Does my child have to have a diagnosis to know if s/he is dyslexic or not?

A. We usually use the term 'assessment' rather than 'diagnosis' when we are talking about dyslexia. Diagnosis has a medical ring about it, and might suggest there is a cure for dyslexia. As you'll see from other pages in this Toolkit, assessment of dyslexia should be a process rather than a one-off snapshot of your child's performance on one day. However, once your child has gone through the process of identifying signs, putting in specific additional help and support (from the class teachers and maybe also from others), if there is no significant progress or if the signs of dyslexia continue, then more detailed formal assessment may be required. There is no one single test however that will confirm dyslexia.

Though there is no cure for dyslexia, dyslexia being a learning difference, there is much that can be done to help, including the use of technology when appropriate. With the right help, ongoing support and accommodations, your child should be able to achieve to his/her potential.

Q. I have been working closely with the school, and teachers are helpful, but when I ask for an assessment they seem to keep putting me off. I feel I need to know whether the difficulties my child is having are due to dyslexia or not. I also feel my child needs to know. Should I arrange for a private assessment?

A. It is important to establish whether your child has dyslexia but you shouldn't have to spend a lot of money on a private assessment. The school should have recommended that your child goes through a staged process of assessment and intervention. A staged approach requires that a child's needs are monitored over time, and that may be why you feel the school are putting you off. Parents should be included in the staged process so you should talk to the school to find out the stage (or step) your child is at. You'll find explanation of the Staged Process of intervention here.

If you are still not happy, then you have the right to request that your child's needs are assessed, and you should expect that to be done within a reasonable period of time. However, this can be done within the school system, and shouldn't involve taking your child out of school, or paying for it privately if your child is in a local authority school.

If your child has already undergone a private assessment that has been carried out by an appropriately qualified individual, then school staff should accept the findings of the assessment, and these should be considered alongside any assessment information that has already been gathered.

Q. After assessment, I was told that my child has, “Dyslexic-type tendencies”. What does this mean? Is he dyslexic or not?

A. The terms used around the subject of dyslexia are continually changing! Where it previously might have been acceptable to use this terminology in the past, the use of terms such as ‘tendencies’ or 'signs' or 'dyslexic-type' which can be potentially confusing for pupils and parents, are not generally used. The Scottish Government definition should allow for a pupil either being dyslexic or not. To what extent will vary along the continuum, so we are generally now more specific and say what the difficulties are, and if they are severe or mild.

It is important is that areas of difficulty have been identified and are being addressed. Areas of strength will also have been identified and these will be developed to help overcome any difficulties. Support is not about a medical diagnosis or label, but it may be important to your child to know. If you have any doubts or concerns about the results of assessment you can request a meeting at your child’s school to discuss the matter in more detail.

1. Services

Q. What help should John be getting at school? We were told a year ago that he is dyslexic but the school don't seem to be doing anything different.

A. It is likely that John will be getting additional support, but that may be quite unobtrusive if it's happening in the classroom. The support for learning teacher will be aware of John's difficulties and be giving support to him as well as others in the class so John might be quite unaware of the support. However if you suspect that John is not getting the support he needs, then you should discuss this with the school. Ensure that John feels the same way as it could be that the support is available, but John is refusing additional help.

Q. My child is being taken out of class for extra help. I'm worried s/he may be missing other more important work.

A. It is likely that your child is requiring additional work that might prove embarrassing in the classroom. S/he is maybe doing some early phonic (sounds) work that will seem 'babyish' to the other children. Children with dyslexia generally need a phonic approach to learning to read if they are to succeed, and s/he may not have 'caught on' to phonics the first time round. They also need a lot of over learning, something that others in the class may not need. If you are concerned, and especially if your child is unhappy about this, talk to your child's teacher. You need to feel reassured that this is for the best.

2. At home/homework

Q. How can I help at home?

A. Probably the best support at home is to listen to your child, and not force them to work at home if this is distressing for them. Find what your child enjoys and/or is good at, and focus on that for much of the time away from school. Ensure that they have a social life too, and enjoy activities such as swimming, gymnastics, chess or whatever, but there is no benefit in keeping insisting on phonics and spelling work for example as they are probably exhausted with their efforts at this during the school day.

Sometimes, however, children are happy to do some work at home and if so, then this is fine. However, do try to limit this, and agree with the school how much homework is reasonable. Sometimes there will be days when your child is very tired after the efforts of a full day in school, and if so, then don't push them too hard. For the younger child, probably around 20 minutes is enough for homework, and for older children, maybe an hour, but children do need to relax, so try to ensure you build this into their lives.

Read to your child, and use story downloads or DVDs. Have the book available and get your child to follow the story for as long as s/he can, but don't worry when they lose the place. The important thing is to try to ensure that your child gets enjoyment out of books, and they don't associate books with failure! CALL Scotland has produced guidance on how to access downloadable ebooks from the Calibre library for the Kindle free of charge.

Play games. With younger children in particular sound games are good. "I hear with my little ear something beginning with (or ending with) ..........." (sound, not letter). Pelmanism or 'Pairs' with sounds and words 'p' matches with a picture of a pot, 's' with a picture of a snake.

Encourage singing, art and other similar activities if your child enjoys these.

Ensure your child is enjoying the games, and doesn't just feel they are an extension of school work. If they don't want to play, then don't make them, but do ensure you find something that they do enjoy and that they are learning from, even though they won't be aware of it!

Q. My daughter is only ten, and though she is dyslexic, she seems to get a lot of homework. She has her phonics and word attack from the learning support teacher, and also has to do her class homework. Sometimes we are at it for two hours, and she gets really distressed after a while. Is this reasonable?

A. Two hours homework is not reasonable for a primary child. You need to discuss this with your daughter's teacher, and agree a reasonable period of time for homework. It is likely that the teacher has no idea that homework is taking your daughter so long as other children may have the homework done in fifteen minutes or less. Because dyslexic children have struggled all day, they may well be 'switched off' when it is home time, and need a complete break for a while. You do need to talk to the teacher, and if your daughter doesn't finish work in the time you agree, then you write a brief message to the teacher, saying how long you have spent, and assuring the teacher that it was you who stopped the work. Getting distressed because homework is not done is counterproductive and is likely to result in longer term or behavioural problems. It is also likely to induce stress in parents and will cause feelings of resentment on all sides.

Q. I am not happy with what the school is doing. Janet was assessed some time ago and we were told she was dyslexic. She is being badly bullied at school and comes home crying most nights. I am at the end of my tether and feel that educating Janet at home is the only answer. Who can help me?

A. Firstly, taking the decision to home educate your child is not one that should be taken lightly. If you are home educating, your child may lack the social stimulus of having friends to support her. Even though you feel you are taking her away from the bullying situation, you will probably also be taking her away from her non-bullying friends. The school should have an anti-bullying policy, and should be implementing it, so if this is your main reason for home educating, then firstly talk to someone from the school management team, and ask what is being done to ensure their policy is working. It is quite likely the school is unaware of the bullying that is going on.

If however, having discussed and allowed time to ensure action has been taken, and you are still set on home education, then it might be helpful to discuss the implications with other home educators. You can contact an organisation such as Schoolhouse for more information.

You will need to let the local authority know about your decision to home educate, and you'll need to have a curriculum set up that you will work to. This doesn't have to be exactly the same as the school's, but if there is a chance that your child will be going back into school at some point, it is important to ensure that they will be able to keep up with the curricular demands. When you contact your local authority education service, find out their policy, as it is quite possible that someone will visit you within a reasonable time to discuss how you will support your child in the home situation.

You should also look at the Scottish Government guidance on home education to ensure that you are fully aware of all the implications. You'll then be able to make an informed decision, but do consider all the implications seriously before embarking on this. Many parents who home educate do this very successfully, but for others it is not the best decision, so do ensure that you are well informed before you decide finally to take this step.

Q. I have been told my child has dyslexia; should I talk to her about it?

A. It is important to discuss this with your child. How do they feel about having dyslexia? Do they understand what it means? Have they any questions that could be addressed by finding out the answers together?

Q. Since my daughter was assessed as being dyslexic, I feel I need to understand more about dyslexia in order to help her. Who can help me?

A. There may be a dyslexia support group in your area, and if so, this is a good starting point. You can then discuss your child's difficulties with others in a similar situation. To find out about local groups, Dyslexia Scotland may be able to help. Contact their helpline (0344 800 84 84) between 10am - 4.30pm (Monday to Thursday) and 10am - 4pm on Friday. School may also be able to point you in right direction, and may run awareness-raising evenings or be aware of relevant upcoming events in the area.

Q. Our boy is in third year at secondary school. He is very dyslexic. He really lacks confidence, and I'm sure he would benefit from more help.

A. It is important for your son to learn to speak up for himself. When he leaves school, whether he goes to college or not, you won't always be there to speak up for him. He needs to develop skills of self advocacy and self awareness so that he can tell people what he requires in order to cope with the demands of life after school. If he is at college or university, he should be able to apply for accommodations to enable him demonstrate his skills and abilities. If in the world of work, he may require additional software on his computer or other accommodation to help him complete his work in the best possible way. He needs to become aware of his own needs and be able to convey this knowledge to others who can help.

Q. My husband tells me he had real problems learning to read at school, and he's still a poor speller. Can you inherit dyslexia?

A. Yes, heredity is generally considered an important factor. Just because one parent is dyslexic, it doesn't mean that their children will be, but it can certainly be a factor.

Further questions

If there are other questions which are of a general nature, we will be happy to add these to the Q and As on this page. You can email the Working Group at toolkit@dyslexiascotland.org.uk. We regret however, we are unable to answer personal questions here. However if you have something that is troubling you, the Dyslexia Scotland Helpline staff may be able to help. You can access them via the National Helpline at 0344 800 84 84 at the following times:

- Monday - Thursday 10.00 - 4.30

- Friday 10.00 - 4.00

Children and Young people: Q&As

Questions children and young people often ask

The questions below are all real questions from real children and young people. Occasionally we have worded the questions slightly differently, but basically the questions are the same questions children and young people ask us. The answers to these questions have been provided by the Working Group, all of whom are involved professionally with children and young people with dyslexia.

A. Each of us is different. Even identical twins as they grow up have little differences. Being dyslexic is about being a little bit different. You don't look any different, and that is why people often say that dyslexia is 'hidden'. Dyslexia is about how your brain works. If you have dyslexia, then your brain functions a little bit differently from other young people. It functions in a way that isn't good for learning to read and write and spell. It affects the way you learn. Learning the sounds and sound patterns in words can be a problem when you are in early primary. If you are older, then you might remember how you struggled with learning to read, how some adults didn't seem to understand why you were finding it so difficult, and why when you started to write stories, no-one could understand them. You seemed to understand what they were telling you to do, but it just didn't seem to 'come together'.

Researchers are learning lots about how our brains work, and are getting more information all the time. Something in the way your brain works transmits the messages in a different way to others - in a way that isn't very efficient for learning to read and write and it often affects numbers as well though not always. Though your memory works perfectly for most things, it has difficulty in remembering what sounds go where, and even when you learn to read, writing and spelling can still be difficult, as you have to work out the order things come in.

A. Dyslexia most certainly doesn't mean you are stupid. In fact dyslexia doesn't really tell us anything about how clever you are or aren't. Dyslexia tells us that you find learning literacy - sounds, words, grammar, structuring stories, remembering some things, recognising symbols for example - difficult. On the other hand, there will be some things where you are just as good and maybe better than others.

Dyslexia is the reason you find some things hard, and it will help you explain to other people why there are things that you are just not good at, and have to work much harder than other people just to get right. It isn't an excuse for not trying however. Though it is tough being dyslexic at times, you do feel great when you finally master things as things involving literacy are a lot harder for you than they are for other young people.

A. Firstly, we wouldn't really talk about 'symptoms' as that would suggest that there is something medical about dyslexia. Though we would suggest that you check out medical factors such as eyesight and hearing with the appropriate specialists so we know these are ok, we wouldn't 'treat' dyslexia like an illness. Dyslexia is about how your brain works, and there is unlikely to be anything wrong with your brain. It just works in a different way from most other people's - in a way that isn't good for learning literacy - especially in the early years. However it is likely also to mean there are different things that you are good at.

There is a 'definition of dyslexia' on the website which explains the likely areas of difficulty. Not every dyslexic person will be the same. We are all different and different people with dyslexia will have a different profile of strengths and weaknesses, so it isn't very helpful to compare yourself with others. Try to see yourself getting better in comparison to the way you used to be, and you'll hopefully see the progress you've been making, and can feel satisfied that you've made progress in spite of your difficulties.

A. Whatever type of support you've been getting in class when doing assessments is the kind of support you should also get in exams. You shouldn't be expected to pick up some kind of extra help just in your National exams or Highers. However, if you are dyslexic and you don't feel you have the appropriate support to enable you to demonstrate what you can do because your reading and writing skills are still weak, then speak to your Support for Learning teacher as soon as possible. You may be able to use a computer, or other assistive means which you'll require to practise before you are in the exam situation. The school will make application for you to do this, so it's important to get it arranged as soon as possible.

Further questions

If there are other questions which are of a general nature, we will be happy to add these to the Q and As on this page. You can email the Working Group at toolkit@dyslexiascotland.org.uk. We regret however, that we are unable to answer personal questions here. If you have something that is troubling you, the Dyslexia Scotland Helpline staff may be able to help. You can access them via the National Helpline at 0344 800 84 84 between 10am and 4.30pm (Monday to Thursday) or 10am - 4pm (Friday). Or you can email helpline@dyslexiascotland.org.uk

Literacy Support Software

Read through this section to get an overview of the software and apps that can be used to support learners with dyslexia. Please note that some of the information on this page is not just about literacy support as there are overlaps in what might help someone. Remember that what works for one person will not necessarily work for everyone and it is important to try a range of assistive technologies to find what works for each individual.

Some learners with dyslexia have strong listening and talking skills. Using audio to record notes removes the pressure of having to write or type. Learners can record notes in class for later revision, an essay or project plan.

A very powerful and motivating technique for some learners who struggle with text is to record audio into digital projects (for example, to PowerPoint or Book Creator/Explain Everything on an iPad). Keep the text to a minimum and use audio for the majority of the content.

Digital voice recording devices

-

Livescribe pen (record and play back audio with synchronised notes)

-

Tablet device or phone

And a wide variety of software / apps that can be used too:

-

Microsoft Word: ClaroRecord Add in for recording audio

-

Microsoft PowerPoint - use the in-built recorder (Insert / Audio / Record Audio)

-

Microsoft One Note - built in audio recorder

-

Notetalker app - to capture audio and images (iOS and Android)

-

Notability - note taking on iPad with audio recording.

Learners can also record answers into digital versions of worksheets. By recording audio answers, a learner can demonstrate knowledge and understanding even if they have significant difficulties with writing. This works well with worksheets in PDF format, where learners can record answers using, for example,

- Adobe Reader (Windows)

- ClaroPDF (i Phone and iPad)

Hamish's story in the Technology Writing section shows how audio notes can be used to answer in worksheets and activities.

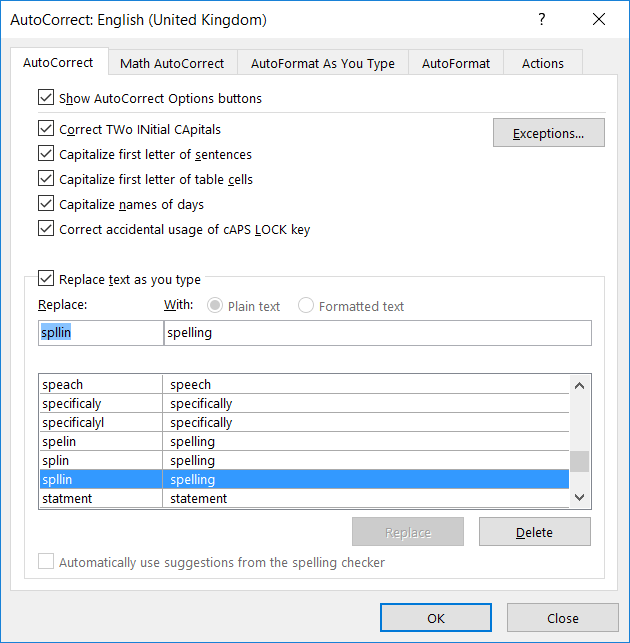

AutoCorrect automatically corrects typing or spelling errors and can be very helpful.

If there are words that a learner consistently mis-spells, adding the wrong spelling(s) to the AutoCorrect dictionary means that no matter which spelling they use, they will always get the correct result. You might think that this is 'cheating', but if a learner has a specific difficulty with spelling, this can prevent them from demonstrating their ability and understanding. Using AutoCorrect will help them focus on the content of the writing rather than the mechanics.

AutoCorrect is built into most word processor and devices; Global AutoCorrect is a specialist tool that can be used for all writing purposes on a Windows computer.

Some learners with handwriting or spelling difficulties find that dictating to the computer or device can be a fast and effective method of writing and interacting with the device. Speech recognition has improved enormously in recent years and is now much more accurate, more forgiving of accents, and does not require training. It is now a much more realistic prospect for learners with dyslexia.

Speech recognition is built in free to all modern devices: iPads, Android, Chromebooks and Windows. Most of these speech recognition tools (e.g. Siri on iPad; Google Voice Typing; Cortana) require an Internet connection. Windows speech recognition and Dragon NaturallySpeaking for Windows do not require an internet connection.

Read how Hamish and MB use speech recognition to address their difficulties with writing.

Visit CALL Scotland's Speech Recognition web pages to find out more about speech recognition.

Many learners have difficulty with memory and organisation. Digital calendars and reminders can be very helpful, for example, to have the school timetable to hand, or for reminders about homework.

Some learners find it helpful to use the 'digital assistants' like Siri on the iPad, Cortana on Windows, and Google Now to give spoken instructions to devices to add events and reminders.

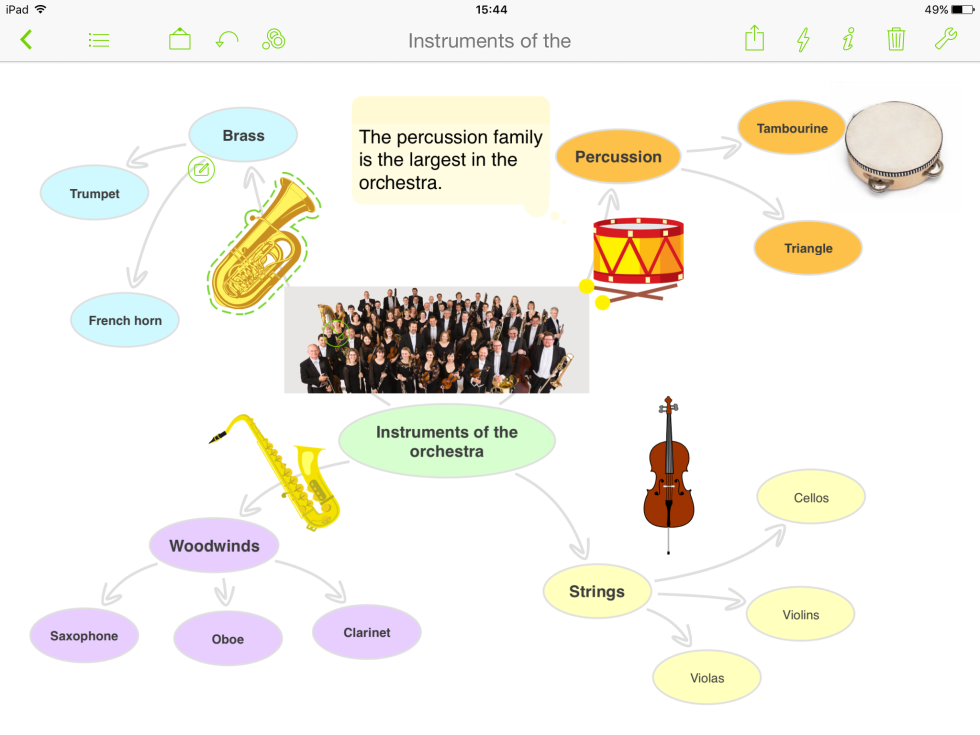

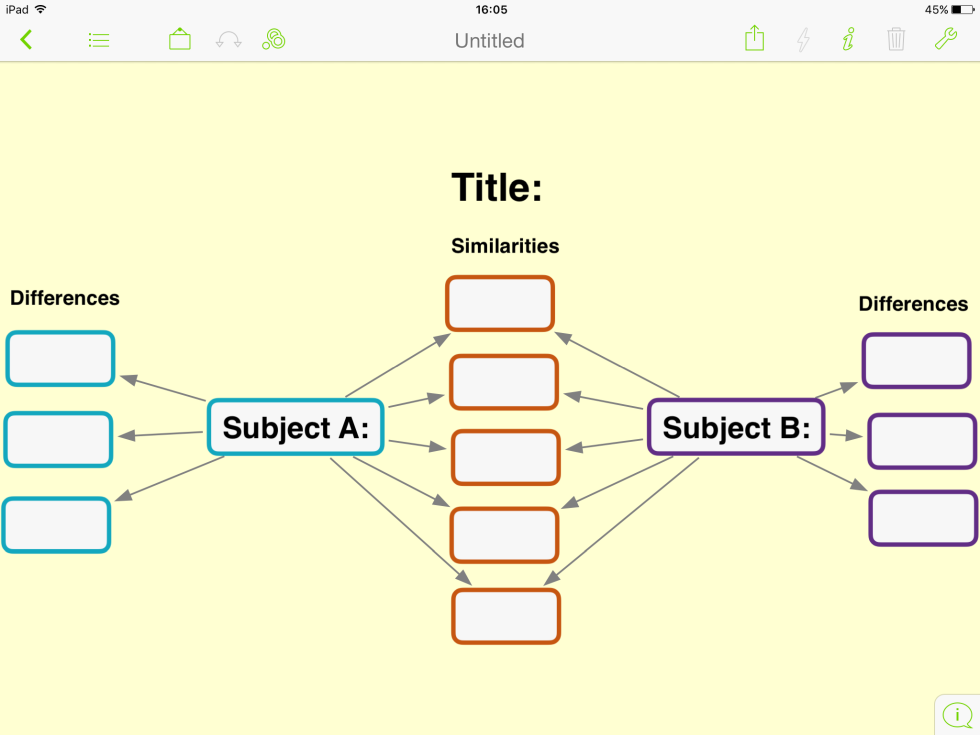

Pupils with dyslexia can find it difficult to organise their thoughts and ideas in a logical and structured way, particularly when it comes to writing activities such as essay writing.

Mind mapping is a simple but effective way to organise and understand information. By using visual prompts, they can help pupils structure their thoughts which can then be transferred to short sentences, paragraphs and extended writing.

What is a mind map?

A mind map is a software program which includes a range of features, e.g.:

- A combination of shapes (sometimes referred to as ‘nodes’, main themes and keywords which are connected by branches

- Branches radiate from a central idea - as the mind map expands topics of lesser importance ‘branch out’

- Images such as clip art and photographs to support visual learning

- Audio notes - pupils can record their thoughts and attach the audio to nodes or branches

- Spell checking

- Options to change font size, font colours and background colours so pupils can customise their working environment

- Options to export the mind map to a word processor or presentation program so pupils can extend their writing around a structured format.

Mind maps can be used to help with:

- Planning and organisation for essays and projects

- Note taking - using either pen and paper or with a software program to take short visual notes

- Study and revision - breaking down information into manageable chunks

- Developing arguments between different theories and comparisons.

Popular examples of mind maps include:

- Popplet – good for creating simple mind maps on the iPad.

- Mindscope – a mind mapping outliner for iPad.

- iMindMap – similar style to Tony Buzan’s mind map for Windows and Mac.

- MindMeister – online collaborative mind mapping.

- MindView – popular among students at college or university.

Using audio to record notes takes the pressure off having to write or type. This can be useful for recording an essay plan, answers to a comprehension exercise or for revision notes. There are many different devices that can be used e.g.

- Digital voice recording devices

- Livescribe pen (record and play back audio with synchronised notes)

- Tablet device or phone

And a wide variety of software / apps that can be used too:

- In Microsoft Word: ClaroRecord Add in for recording audio

- In Microsoft PowerPoint - use the in-built recorder (Insert / Audio / Record Audio)

- In Microsoft One Note - built in audio recorder

- Notetalker app - to capture audio and images (iOS and Android)

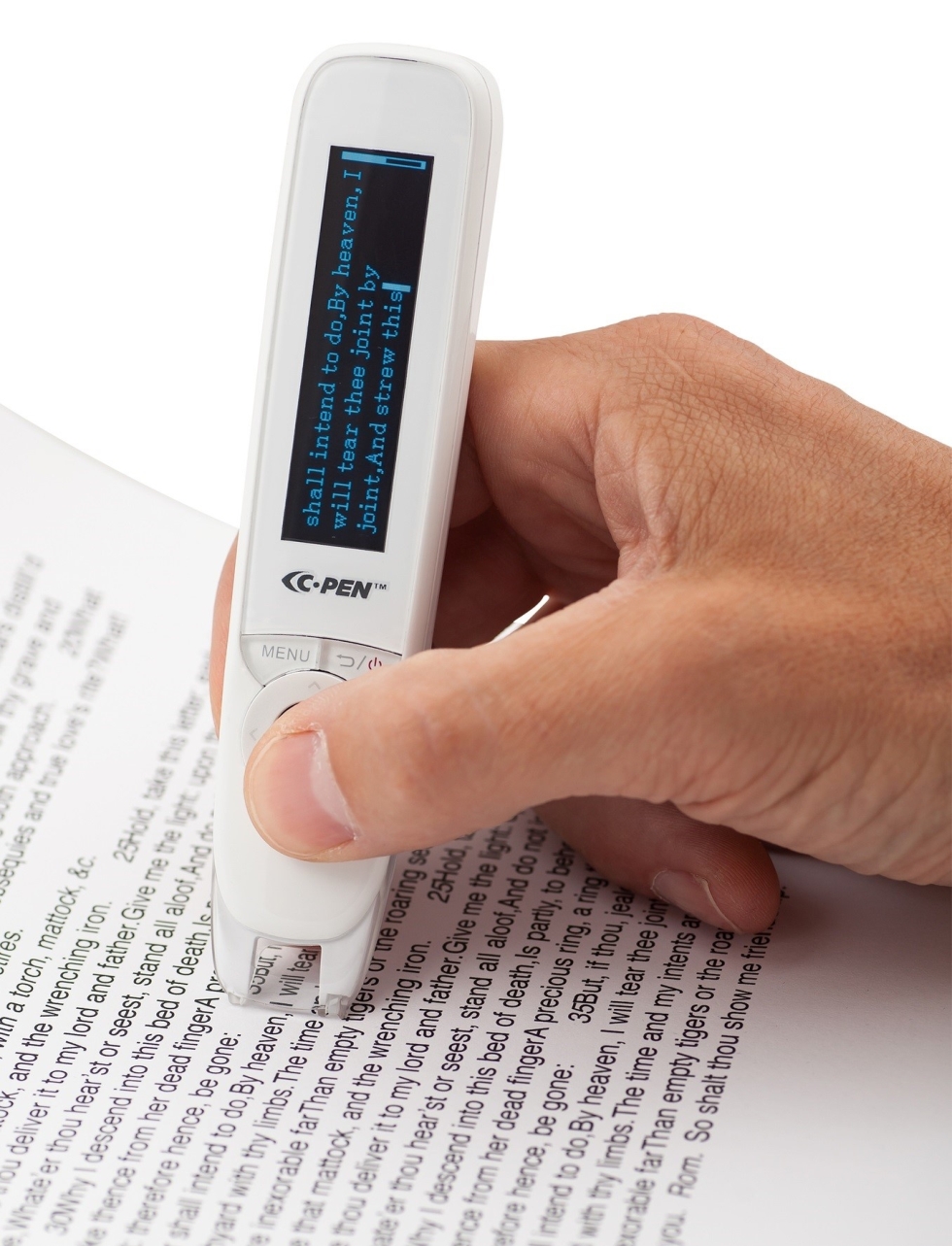

Reading Pens are small pocket-sized devices that scan and read back single words lines of text from a variety of documents, such as worksheets. They are lightweight and portable and some learners find they can improve understanding and independence.

The reading pen voices are not as good as the voices in computers or tablets, and the text is not always read accurately. Possibly not the best option if the learner relies on a text reader, but a simple, practical tool for occasional support.

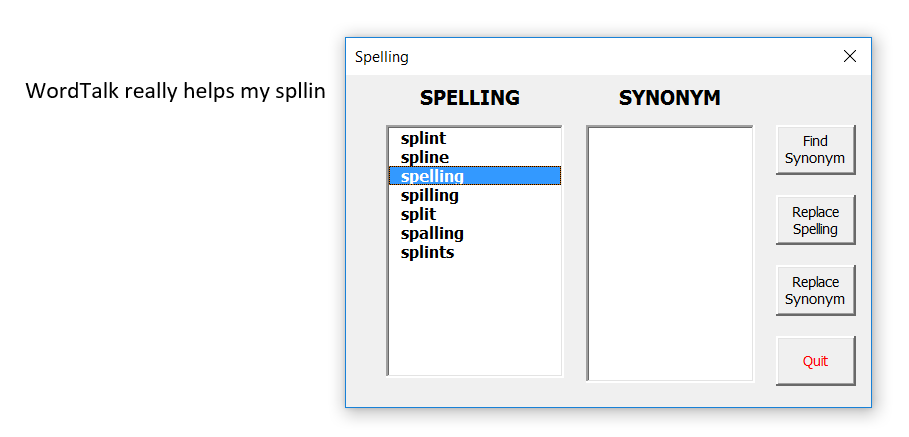

Spell checking is an integral part of writing but for dyslexic pupils who find spelling difficult, it can be frustrating, challenging and, in some cases, embarrassing to the pupil.

Spell checkers are available as small pocket devices (such as the Franklin spell checker) or as a stand alone software program, such as Ginger or Grammarly. Spell checking can also be a component part of a word processing program, e.g. Microsoft Word or Pages - misspelled words are highlighted with ‘red underline’. Microsoft Word and Pages also includes additional tools such as a thesaurus and synonyms to support the writing process. The free WordTalk add-on for Word reads out the spellchecker list to help learners identify the correct word.

Portable Handheld spell checkers

Franklin (and other) portable Spell checkers have been around in various shapes and sizes for over twenty years, and they are still very useful, particularly those that provide speech feedback.

Benefits of portable spell checkers

- They are portable;

- They are reliable;

- They are efficient and easy to use;

- They have a long battery life;

- They are available for children and adults.

There are also disadvantages, for example, it is difficult to transfer a corrected spelling to a word processor and not all portable spell checkers include grammar or context checking.

Online spell checking

Online spell checking works by identifying misspelled words in the context of a sentence. Most will work alongside writing programs providing spelling support for writing essays, emails and even writing on the web, e.g. social media.

Benefits of online spell checking

- Provide spell checking within the context of a sentence

- Can discern between similar sounding words such as ‘hear’ and ‘here’

- Normally offer accurate correct suggestions to the misspelled word.

For more on spell checkers, including spelling programs and spelling activities visit the writing section of the CALL Scotland Dyslexia website.

With speech recognition you can speak directly to your smart phone, tablet or computer (using a microphone) to do all the functions described in the Note Taking section but the difference is that what you say will appear in words not just as an audio file to listen to.

The benefits of this are:

- Unlocks the potential of users who are very able orally but struggle with writing / word processing

- User does not have to worry about spelling mistakes

- Much greater volume of work achieved as you can speak faster than typing

- Greater independence for user - no reliance on a human scribe

- Provides a confidence boost to dyslexic learner who may not be able to produce a legible piece of writing

- Can be used in any location if using portable device (and an internet connection is available)

For a comprehensive round-up of everything you want to know about speech recognition, please refer to CALL Scotland Speech Recognition website.

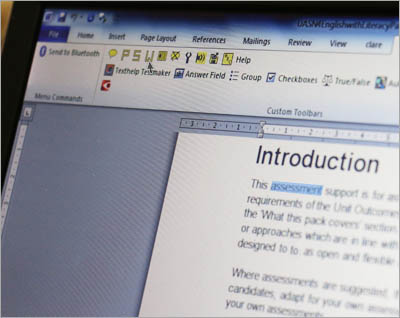

A 'text-to-speech' program or 'text reader' on your computer or tablet reads text from a document or web page to you using a computer voice.

For pupils who struggle to read, a text reader is an invaluable tool as it can help pupils to hear words spoken aloud by the computer, including tablet devices such as iPads and Androids. In addition, some text readers include colour highlighting which synchronises with the speech, helping pupils to focus on words and sentences as they are read aloud. This can be of particular benefit to pupils who experience visual stress.

A text reader can help pupils who:

- Read slowly or with difficulty;

- Get tired easily or experience visual stress;

- Find it hard to concentrate on words and sentences.

Text readers can help pupils to:

- Proof-read their writing;

- Identify spelling mistakes or typing errors;

- Understand what they are reading - improve understanding of sentence structure, sense and meaning.

Text readers can read a wide range of formats including:

- Text on web pages, including social media;

- Word documents, PDFs and email;

- Scanned materials such as books, magazines and other paper-based format. Text readers require scanned material to be ‘Optical Character Recognised’ (OCR) the process which converts paper text into digital or editable text.

Examples of text readers include:

- WordTalk - a free Add-in for Microsoft Word;

- Natural Reader - free text reader for reading a range of formats;

- Orato - free text reader.

- AT Bar - free text reader which can also read Maths equations and symbols.

Visit the CALL Scotland website section on ‘Text-to-Speech’ to find out more.

Keyboard skills are essential if anyone is to make effective use of a computer for learning and work. Learning to type can greatly reduce the need for handwriting which is often seen as a challenging area for those with dyslexia.

The main benefit of having good keyboard skills is that errors and spelling mistakes can be corrected by word processing programs more easily than handwriting. Keyboard skills can also improve physical dexterity as it involves a series of patterns and finger movements – once learnt, it is never forgotten and is a useful skill for school, college, university and for working life.

Modern day typing tutors are engaging and use a multi-sensory approach with audio, images, animations, text and often a series of interactive lessons. The Dyslexic.com site provides helpful guidance on ‘dyslexia friendly’ typing tutors as well as some helpful tips on deciding the most appropriate typing tutor for your pupil.

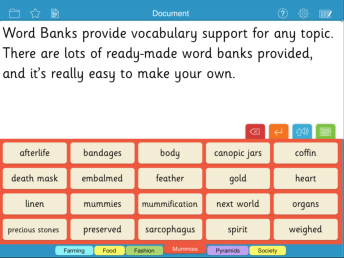

Word banks are lists of words, usually in the context of a subject, to support children with their writing. Word banks will vary according to the age of the pupil and the writing task.

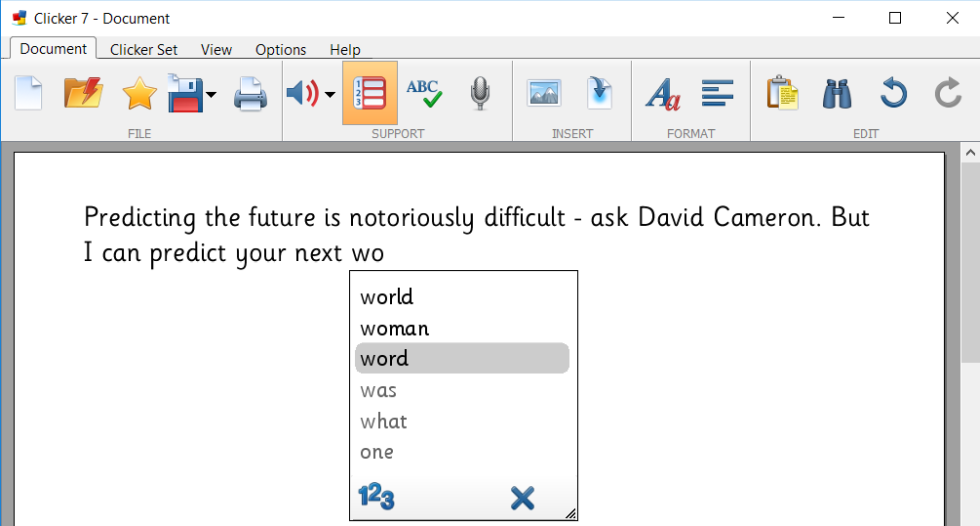

Programs such as Clicker 7 provide a tabbed word bank allowing pupils to click on words which are then entered into Clicker’s word processor.

Features of a word bank

- You can create age-appropriate and subject specific word banks.

- You can click on a word to hear it spoken aloud.

- You can have multiple topics related to one word bank.

Word banks can help to improve writing accuracy and boost confidence.

Word prediction is a useful tool that can benefit both young and old learners with dyslexia.

What is word prediction?

- Word prediction predicts the word or phrase after the first or second keystroke is pressed and predicts a list of associated words;

- Words are predicted in the context of the sentence by predicting a list of associated contextualised words following from the last word, i.e. ‘next word prediction’;

- Words predicted in a list can be spoken aloud so pupils can see and hear the correct word before making a choice.

How can word prediction help?

Word prediction can help improve typing speed and accuracy because the writer need only type two or three letters and then pick the word from the list. Most word predictors let you listen to the words to check before you choose. Some word predictors can accept phonetic spellings, so you don't need to type the beginning of the word accurately - this can be very helpful for some learners with dyslexia. Word prediction can increase confidence when writing essays, projects etc.

You can create curriculum specific lexicons or word lists - e.g. a custom lexicon on the Roman Empire, The Greeks, or a lexicon for political or sociological theory. This allows words which are associated to a particular subject to be predicted more frequently and in context and can be very useful for particular curricular areas where long and/or difficult-to-spell words are used.

Examples of Word prediction programs include:

- Penfriend - also predicts in Gaelic and other European languages (also available on a USB pendrive).

- Co:Writer: there are two versions - a standalone version which works from the desktop (Windows and Mac) or a cloud version, Co:Writer Universal, which works via a web browser and works across a range of devices. Co:Writer is also available as an iPad app.

- WordQ: similar to Penfriend and Co:Writer - also available as an extension for the Google Chrome browser.

Working in partnership: Q&As

Questions professionals have asked

The questions below are questions that members of the Working Group have been asked. There may not be one single answer, but these are the answers that were agreed by the group. The working group has organised the questions under headings but there is considerable overlap between headings.

Q. Often we find with learners that are dyslexic or that might be, there are behavioural problems. Many staff are unsympathetic to the dyslexia because of the extreme behaviour which disrupts classes and prevents others from learning. Who should be dealing with this as many teachers don't see these youngsters as their responsibility?

A. We firstly need to get a full picture of the young person and their needs. It is important to work with the family - that is, mother and father - even though they may be living apart. Both parents will be important to the child, and may be able to help considerably. If parents are apart, the child may be playing one off against the other, so just by agreeing a joint approach, this can help. Consider the school setting. Are there problems with some teachers but not with others? Are there problems in some subjects and not in others? What seems to be causing the problems in specific subjects? Is the youngster simply not coping?

We also need to look at how the child or young person is behaving in the community. Are there problems outside of school? Is the young person offending in the community or are the behaviours only exhibiting themselves in school? All of these questions are important and can offer explanations as to why the young person is not able to cope within the classroom.

If the problems are wider than the school, then it is important that other services involved work with the school before things escalate out of control. The principles of GIRFEC and the recommended procedures should come in so that the young person is put at the centre, and there is no 'out of sight, out of mind' philosophy.

Getting back to the original question, these children are everyone's responsibility and their safety and progress is dependent on their difficulties being discussed and procedures being put in place to ensure that they have some strategy in place for when they feel they are about to 'kick off'. Policies are in place in most schools to ensure that the young people don't end up out of school and on the streets, but every so often things go awry. All schools and staff need to be aware of the procedures that are in place for dealing with students who have behavioural difficulties, with or without dyslexia.

Q. Michelle, a Primary 5 learner, has dyslexia. She also has auditory processing difficulties. Our Hearing Impairment service don't feel this girl has anything to do with them as she doesn't have a hearing impairment. Who else is likely to be able to help?

A. We would begin with assessment or if this has been done then give the previous assessment detailed examination to see if there is anything else that can be done. How is Michelle's phonic knowledge? If she has difficulty with auditory processing then she may have missed out on a lot of learning about phonics and phonology. When the gaps are identified, then very highly structured multisensory teaching of phonics might now work if it is done in the 'right' way - not by repetition of what has already failed for her. What about her concentration? Does she have difficulty with that? Again if she has difficulty with auditory processing, then she may 'switch off' from time to time, and strategies to keep Michelle on task will help. Assessment and the building of a profile of Michelle's learning and the gaps that have emerged should guide the next stage.

There is some recent evidence that the magnification of sound for children with Michelle's type of difficulty might help, and so this should be considered. Assistive listening devices (classroom FM systems) may reduce auditory processing variability by enhancing acoustic clarity and attention. The service for Hearing Impairment should be able to advise though it is appreciated that their priority as far as teaching is concerned will be for the children who do have hearing impairment.

Q. James in S2 of our school would benefit from the use of a laptop for word processing. I've phoned the authority who say this is standard equipment nowadays and the school should supply this. I'm told the school budget hasn't got enough to pay for this.

A. Does your authority have an IT service or an assistive technology service? They may be able to help out with a short term loan. This would at least give you time, and would reassure everyone that this equipment is needed. We suggest that your school should plan on building up a bank of computers. Not too many, as computers do go out of date, and you need to ensure they are going to be used. It might be an idea too to suggest to your school cluster that there should be a bank of computers that the schools could share. The schools would of course have to agree on what would be a realistic sum to put into this. However computers are standard equipment and there is likely to be a demand for appropriate hard and software so building a bank of such equipment would be a sensible measure.

Q. One of our children has some specific difficulties, but we don't believe it to be dyslexia. The child is quite slow, and doesn't read well, but the class teacher who is very experienced thinks the child is just not very bright. Parents have recently come to the school, and said they are taking the child for private assessment. I'm not sure that the school should accept this.

A. On occasions parents may approach the school and wish an assessment to be carried out. If school staff are aware of difficulties then these should previously have been discussed with parents (and the child if at an age and stage when s/he can understand). The child should have been put onto a staged (or stepped) process of intervention.

Paperwork should be in place, and this can be discussed with parents. If parents are not happy with the school's process of assessment and planning this may result in them having their child assessed privately. This should not be necessary, and parents do have a right to insist on a full assessment of their child's needs within the school and local authority system, and the school must comply if this is the case.

On occasions, parents may have their child assessed without prior discussion in school. Some schools feel they should not accept an assessment that they have not agreed to. This is unhelpful, and could result in parents (and the child) feeling alienated, additional workload being incurred by the school and local authority and needless stress on all sides. In reality, if the child has been assessed by an appropriately qualified individual, then school staff should accept the findings of the assessment and these should be considered alongside any assessment that has already been gathered. The school should be prepared to work with parents and the child in the circumstances, thus ensuring the learners’ needs are met.

Writing

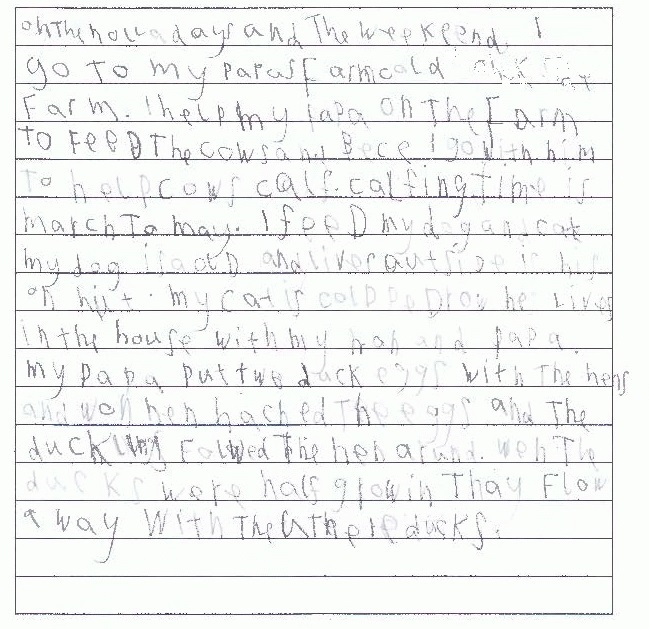

Learners with dyslexia may:

- write slowly and with great effort

- produce writing that is untidy or difficult to read

- struggle to spell accurately;

- be much better at talking about a subject than writing about it

- be reluctant and try to avoid writing.

Technology can address all of these support needs. In this section we give three examples to illustrate how technology can help learners who have different challenges with writing.

CALL Scotland's Supporting Writing Difficulties infograph provides a step-by-step guide in the form of a question and answer checklist helping you to identify problems and suggesting a range of practical technology focused solutions to support pupils with writing difficulties.

CALL's Dyslexia Writing page offers more detailed advice.

A personal digital device can be very helpful for learners who have difficulties with handwriting or spelling.

Barry is in P7 and has difficulties with handwriting and spelling.

There was a desktop computer in the classroom, but using it required Barry to leave his peer group and go to the back of the room, which did not help him to participate in class.

Barry was provided with a small laptop computer with the Co:Writer word predictor to support his spelling. Barry and the class teacher and learning assistant were shown how to use the technology. Barry also worked on his typing skills with Doorway Online.

After 10 weeks, his class teacher completed an evaluation of the intervention:

What impact has the netbook had on the pupil’s ability to access the curriculum?

There was an immediate impact on Barry’s enthusiasm and attitude to attempt and produce work. Used for:

- Word processing: planning, drafting and publishing.

- Barry is more able and willing to work independently on these three steps without an adult scribe.

- Barry is eager, and able, to be involved in adding to his Co-writer word bank.

- Typing answers to spelling activities – a task which Barry dislikes when he is writing by hand. He now produces work of a higher level.

- Spelling has improved.

Barry’s difficulties with handwriting and spelling were having a negative impact on his education, and also on his well being. The laptop addressed his handwriting difficulty, while the word predictor helped him to improve his spelling. The combination, plus the support from his teacher and classroom assistant, improved his well being.

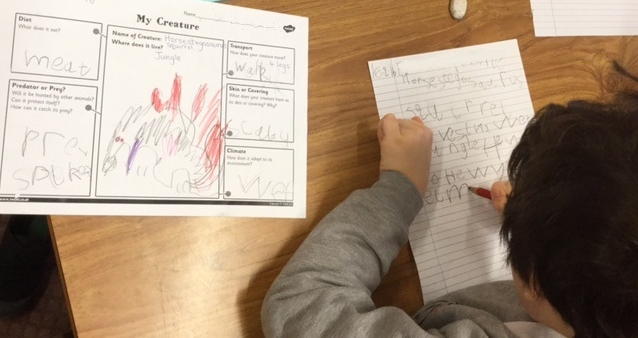

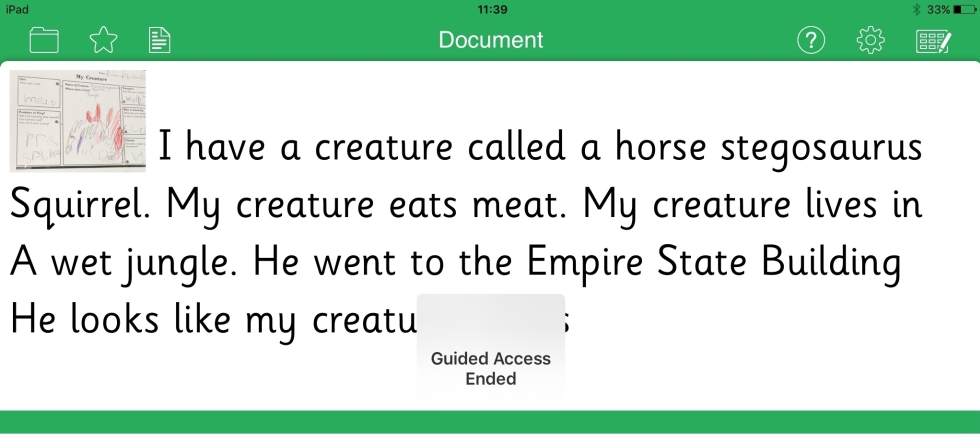

Poor handwriting can be really demotivating. John is in P2. He has Autistic Spectrum Disorder and also struggles with handwriting and literacy.

A sentence building activity was created using Clicker Sentences on an iPad. John was able to produce a much more satisfying piece of work. Clicker Sentences provided word banks with appropriate vocabulary for the learning task and read back his text as he wrote. He was kept on task with the built-in Guided Access on the iPad.

Find out more about iPads and tablets from CALL Scotland's Using the iPad to Support Dyslexia poster, iPad Apps for Learners with Dyslexia, and Android Apps for Learners with Dyslexia.

Some learners have strong oral skills that they can use to overcome difficulties with writing. This Case Study shows how one learner used Dragon Speech Recognition to overcome significant difficulties with writing. The example is from the Talking in Exams Report, from CALL Scotland.

"MB is an S1 pupil who transferred to this school at the end of February this session. M has quite significant barriers to learning, particularly dyslexia. He also has a variety of social and emotional needs and has very low self-esteem. It became quite clear early on that M would not be able to properly access the curriculum unless it was adapted for him. His written work was very poor and he was extremely reluctant to answer out or speak out in class.

"M became part of the ICT group, which meets with me every Tuesday afternoon. He quickly built up a [Dragon voice] profile on his assigned PC and was able to complete written assignments in English, within a short space of time. M is a very articulate pupil with good ideas and a great imagination and he soon realised that he was able to commit these ideas to paper, via dragon software. This has really increased his self-confidence as he is now able to use the software for homework, powerpoints, extended pieces of writing, etc.

"Staff know to send him to the ASN base to complete pieces of work using the software and M now has the confidence to ask staff if he can come to the base, whenever appropriate. He has a sense of independence with his class work and can see that there are other pupils in school just like him, who need an extra level of support. His mum has visited the base to see M working on dragon and has recently purchased the software for her own laptop at home.

"M showcased his abilities on dragon software at the North Lanarkshire Learning Festival in May and accompanied me to the CALL Scotland seminar earlier this month. His self-esteem has also increased as a result of these visits as he feels that he is "good" at something and that others want to learn from him.

"His parents are delighted at the progress he has made since March this session and they too feel that dragon software has been the "key that has helped to unlock M's real abilities".

MB dictated this using Dragon:

“Dragon has helped me so much since I started using it.

Ever since joining the school Dragon has helped me get through all my work and helped me to do the best I can. It is so easy to use I’ve taken to it so well. When I first started at the school I did not know what Dragon was. Dragon has helped me with spelling and vocabulary.”

Find out more about Dragon and Speech Recognition from CALL Scotland's Speech Recognition pages.